The Ways of Seeing

‘Finding Vivian Maier’, the award-winning documentary that catapulted Vivian Maier’s brilliance as a photographer into public consciousness, is a meditative study of where the audience is placed in the spectrum of anonymity

Praveena Shivram

‘The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life’

– William Faulkner

There is an undeniable thrill to anonymity that even while it covers you up in a cloak of anticipatory discovery, it leaves behind a state of breathless excitement, at it being yours and yours alone, like the lines etched inside your palms, hidden either in a tight fist or in a casual downward slant, but hidden nonetheless. It’s like a secret, that becomes such an intrinsic part of your personality, that you forget it exists as something separate, till the secret itself becomes your life. Obviously, I perfectly understood Vivian Maier.

She was ‘discovered’ in 2007 by John Maloof, who was trying to collect material for a history book he was working on and ended up buying a box full of undeveloped film at an auction house in Chicago. When he developed some of them, he realised he had stumbled upon a street photographer who would eventually be hailed as (albeit controversially) one of the greatest 20th century American photographers, redefining the very texture of street photography with her candid, powerful eye for the unique. There was a ‘rawness’ to her images that somehow found its power in its sheltered existence – because, Vivian was a nanny who obsessively shot photographs that she wouldn’t show anyone. She spent all her life taking images, wooing images, befriending images, courting images and then locked them all away in boxes (at last count, there were 100,000 negatives), some of which she kept in a storage facility, and some that eventually found their way into auction houses to financially sustain her. When she died in 2009, a part of her compulsive need for anonymity died with her, and her images began to speak.

Somehow, as I looked at her images – some arresting, some humorous, some disarming, some depressing and almost all of them hypnotic and penetrating – I could not help but feel a sense of loss, like I had entered a funeral I hadn’t been invited to, and yet I couldn’t leave. It was much easier to embrace the loss and allow it to seep into my skin than not to have felt it at all. My engagement with Maier’s images was like the curious case of Benjamin Button – I was falling in love backwards. I was mourning its loss even before I could fully appreciate its presence in my world (because ‘life’ would be too limiting a parameter). When we stumbled upon this story – Maloof, along with Charles Siskel, eventually made this into a compelling documentary ‘Finding Vivian Maier’ that has been widely screened – it seemed like a delicious proposition to understand this often overestimated but really understated bond between the artist and the audience. Vivian, in her resoluteness to keep this under wraps, to keep her identity itself under wraps – some of the best moments of the film are these, when Vivian apparently introduced herself to someone as a ‘sort of a spy’ or when she insisted on giving obviously generic names that everyone knew to be false or her apparent ‘French accent’ – and this wide publicity that she now enjoys are oddly contrasted. The ‘audience’ when it arrived, was not of Vivian’s own making, and to speculate what the audience of her own making would have been, seems like a futile exercise.

*

In a 2013 interview for Indie Wire, Siskel says, ‘Art has to be seen. And Vivian’s art wasn’t seen in her lifetime. Her photographs were seen by a wide public. That’s part of what it means to share your work publicly. She didn’t do that, so we’re thrilled to see audiences embracing her photography and her story.’

To be honest, her story is quite fascinating, simply because the clues she left behind of the kind of person she was are entirely to be found in her photographs. No amount of conversation – and Maloof has painstakingly tried to find her friends and family to interview for his film (and probably for copyright purposes too) – tells you much about Vivian – she almost revelled in creating different personas: that she hoarded newspapers like Gollum and his ‘precious’ and stacked her rooms up with piles and piles of it that even travelled with her when she moved from one place to another; that she was a ‘pack-rat’ with boxes and boxes of coupons and trinkets and bills; that she played at being a journalist, recording live interviews with people in supermarkets about the political climate then or at events; that she took a year off to travel through Asia; that she was eccentric or ‘beyond eccentric’ as someone says in the film; that she was cruel as one child she looked after reveals, and that she always had the camera around her neck and always took photographs. What did Vivian think about, what did she feel, what moved her, what touched her soul, what made her smile, what were those things that filled up the blank spaces between her breaths are only to be discovered through her photographs. Because, and thankfully for her, she did not belong to our world of hyperlinks and Wikipages.

As Maloof says in the Indie Wire interview, ‘Vivian is one of those people that becomes mythical. Nobody has moving footage with dialogue out there. Nobody knows her that well.’ And, to me (as with audiences around the world), that is part of the charm of Vivian’s photographs. That I don’t know, I don’t know how this artist’s thought process functioned, I don’t know the life experiences that made up this person, and yet I have this large body of work to sift through, to freely gallivant across limitless imagination and create at will superimposed emotions that resonate with me. That I am, unwittingly, at the centre of this creation because how I interpret it is utterly my own. There is no one ‘curating’ my emotions, no ‘information’, other than the peripheral, directing my vision, no ‘interview’ with the artist colouring the landscape of my thought, and no memory even – that of the artist or the subject photographed – hindering my connection to the image.

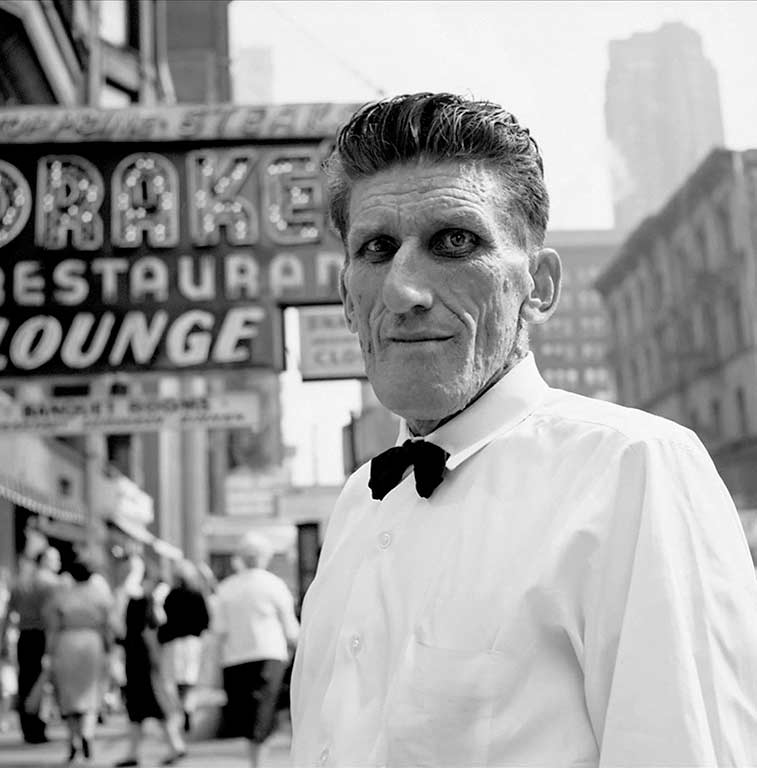

In the film, contemporary colour photographer Joel Meyerowitz makes an interesting observation. He says, ‘As she was photographing, she was seeing just how close she could come into somebody’s face. That tells me a lot about her. She could get them to accommodate her by being themselves. She could generate this moment and then she is gone.’

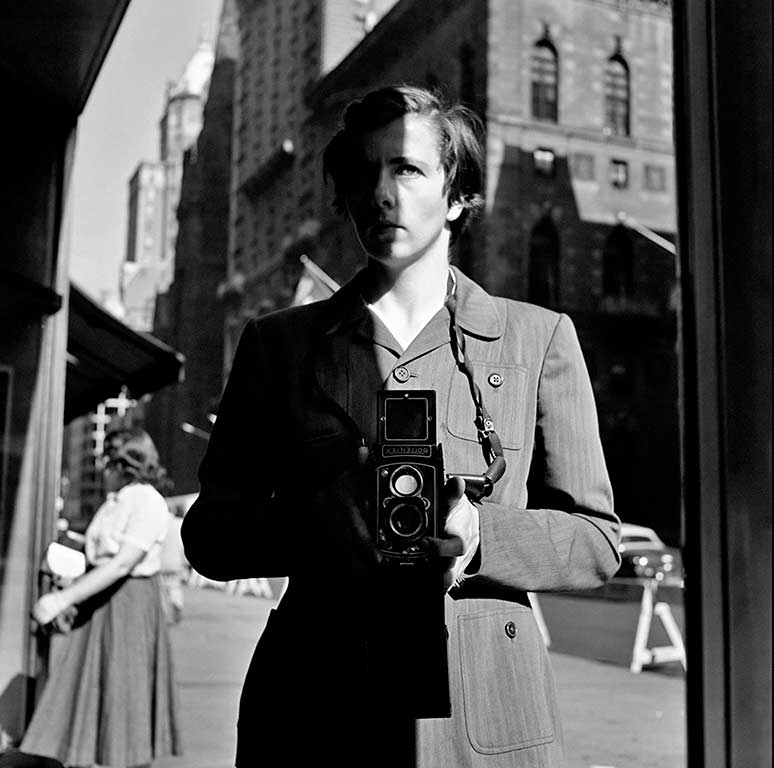

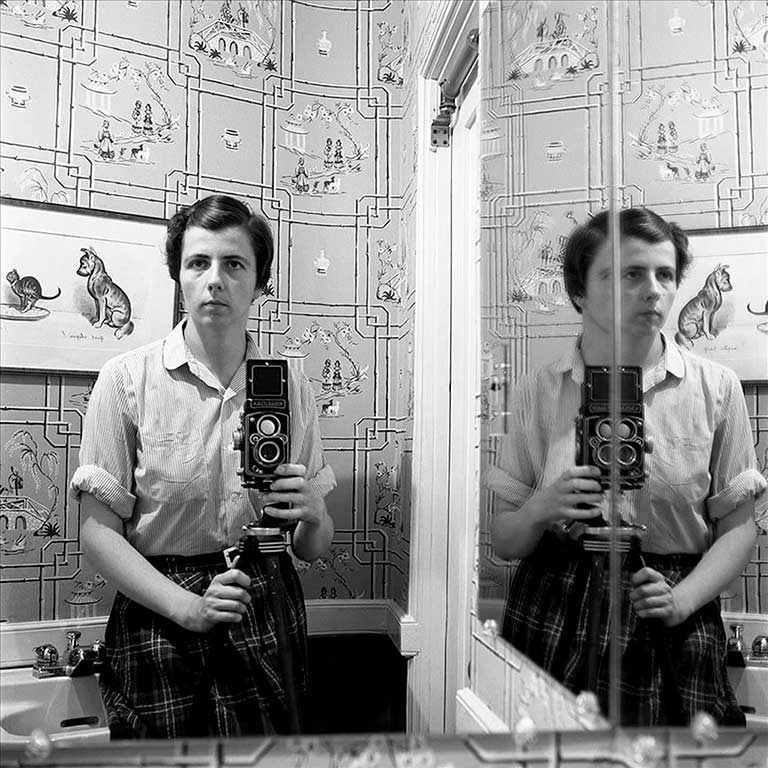

It is exactly this motif of transience that sticks to you with magnetic precision. And the fact that the camera Vivian used – a Rolleiflex camera – always at chest level, allowed her eye-contact with her subject. You are seeing what the photographer is seeing, you are seeing what the subject is seeing, and within that mix is the realisation that they are both, therefore, aware of what the audience is seeing. What is ironic is that the transience rests with the photographer and the subject – both strangers – and the permanence rests with us – the viewers.

*

I stumbled upon the ‘Art of Photography’ with Ted Forbes, who talks about the many nuances of photography on his YouTube channel, quite by accident, and discovered there was a lawsuit over copyright for Vivian Maier’s images, with a lawyer claiming he has found the closest next of kin to Maier who becomes the rightful heir to these images – and the money it is making. In one of his episodes dedicated to Vivian’s images, Forbes brings up an important point – that every artist reserves the right to edit his or her work. And that could go both ways – how you want to ‘print’ your photographs, even if you don’t print them yourself, and how you want to showcase them to the world. In Vivian’s context, we are seeing a wide selection of images, printed and selected by those who neither knew the artist nor were intimately privy to the politics of her time. Vivian, herself, it would seem, was completely disconnected with the economics of her craft, though the film reveals there was at least one attempt by her to have her photographs printed and sold. In a letter written by Vivian to a studio in France, she expresses an interest to do business with the printer.

In a 2014 interview to American Photo, Maloof explains, ‘We don’t think anything happened with it. We know that this person printed her postcards before, though, because I have them. They’re French landscapes, they’re of the era, and they’re not printed by her. So we don’t know if this letter we found was ever completed or if it’s just a draft, or if it just didn’t work out.’ But it is Siskel’s view that probably comes closer to the truth. ‘…But for us it pokes a hole in this very romantic idea that Vivian was an artist creating art for art’s sake, as if she set out from the very beginning to be this mystery woman (as she does describe herself), who would labour for decades creating a huge body of work only for herself, that should never be seen, never be tainted by public consumption.

That romantic idea is ultimately less interesting than the truth –which for us is more compelling – that Vivian wasn’t able to share her work for a variety of reasons and because life is messy and complicated. She was probably partly intimidated by the idea of sharing her work for the same reason any artist is. They don’t want to be rejected. They don’t want criticism. The cost and labour involved in processing her work would have been significant. The biggest factor was probably time. Over time she got used to saying, “Well, maybe someday I’ll get around to printing this.” Or “Eventually this will happen, but for now I’ll just continue to take photos.” Years turn into decades and then eventually she has this enormous body of work which she tragically didn’t get to share during her life: tragic not because of the fame – who knows how Vivian would have reacted to that, being as private she was – but just to know that other people have been moved by what she saw through the lens and have come to appreciate her work and that she did find an audience. She didn’t get to experience that during her lifetime, but thanks to John’s discovery, it has happened now and sort of closes the circle.’

Except, I am not too sure of that, because some circles are meant to exist in waves or loops, they are meant to contain as much as they are meant to release, and they are, most of all, meant to know the point at which the circle really began. As much as Siskel believes ‘art has to be seen’, I think Vivian’s story might just be that confounding exception to prove that even when art is not seen, it remains – unconsciously and unpretentiously – quite simply, art. Even when hiding inside boxes in storage or inside the boxes of the mind.

All photographs by Vivian Maier,

Image credit: via YouTube.

Interview sources:

http://www.americanphotomag.com/interview-john-maloof-director-finding-vivian-maier#page-7

Share