A Watchful Eye

With motion and infrared sensors, remote activations and the capacity to capture images for months on end, camera trapping subverts the art of photography and assists researchers concerned with wildlife conservation

Godhashri Srinivasan

In 2010, Russian biologists trekked across snow-capped mountains and through freezing Siberian terrains, collecting data for the first real survey of snow leopards. Their mission was to set up automatic cameras across the Altai Mountains and capture pictures of its snow leopards. The animals were elusive and incredibly hard to spot. And in the next 1 and a half to 2 years, the biologists weren’t able to photograph any.

But then, they came – a sniffing nose, a darting, sleek body, two bright eyes staring straight at the camera.

A snow leopard in Russia’s Sailyugem national park. Image Credit: Sailyugem National Park/WWF Russia.

In Bogota, Colombia, after the end of the armed conflict and demobilisation of the FARC rebels, Angélica Diaz-Pulido and her team of biologists travel into Colombia’s forests for the first time in many years. Their aim is to catalogue the wildlife in these unexplored areas to protect it, and in some ways, as Diaz-Pulido herself says, ‘rediscover their country’.

In the film by Ryan Ffrench, titled Eyes in the Forest, after setting up camera traps, Diaz-Pulido and Jorge Ahumada of Conservation International analyse the black and white photos lit with functional, not artistic camera flash. They come across a picture of a passing jaguar. The animal’s patterned rear is the only thing that’s seen. But Diaz-Pulido is thrilled. ‘It may not be artistic’, she says, ‘but the jaguar passes right there, where we put the camera. What an accomplishment. The conservation of the jaguar is the reason for all my actions. From a scientific perspective, jaguars are considered an umbrella species – when you see them it is an indication that this ecosystem is functional’.

Jaguar. Image Credit: © Angélica Diaz-Pulido / Instituto Humboldt.

Wildlife researchers and biologists all over the world follow trails, decipher scratch patterns on trees, study animal droppings and track pugmarks to find the perfect location for their cameras. After this lengthy, exacting process, they mount protected cameras on trees or slightly above ground level. After a crawl test – in which researchers get down on all fours and crawl in front of the camera to make sure it’s accurately positioned – they return to their camps.

Sumatran tiger. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the wilderness, at the mercy of rain or snow, these cameras click silently sensing heat or movement. If their protective cases do not hold, the camera might not work. If the positioning was even an inch too high or low, animals might fall out of frame. Even a small error could invalidate several hours of work. Despite it all, the pleasure of a good camera trap photograph is not a profound statement on existence, but just the slightest hint of it. It is the joy a researcher finds at the definitive, but small snatch of a rare bird’s wing at the corner of their photograph.

A wild boar in Trongsa district, Bhutan. Image Credit: Emmanuel Rondeau/Conservation International.

‘Biologists have forgotten to communicate what we do’, Diaz-Pulido says, ‘and that is a big part of the reason why most people in the city aren’t connected to nature’. Born in a city herself, she admits she has lost the ability to see in the forest. ‘Camera traps gave me that ability back’, she says.

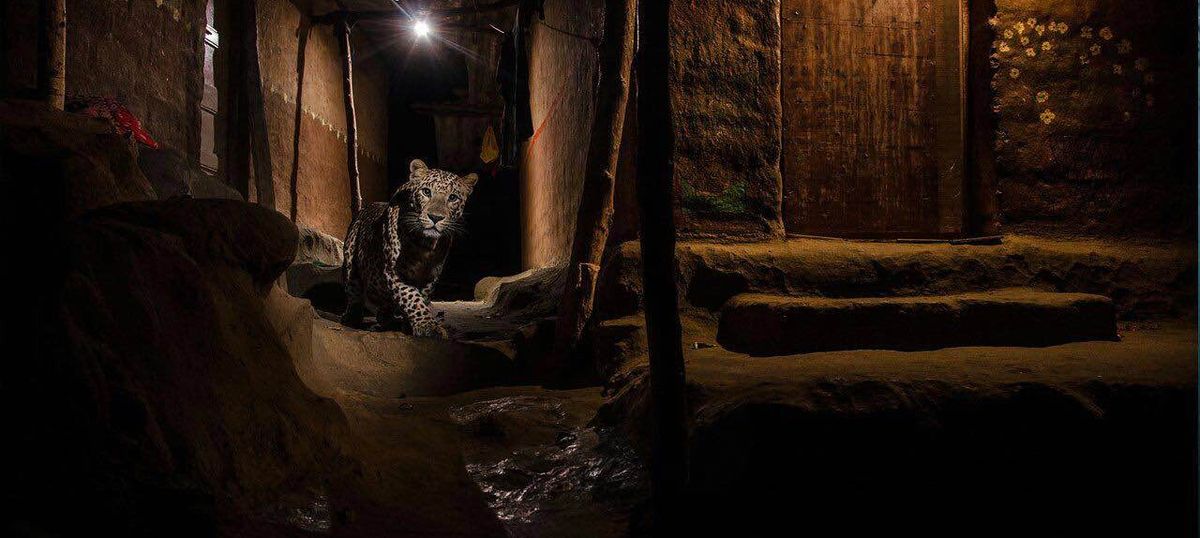

Across the world, but much closer to home, in Mumbai, camera traps caught a different picture. In Aarey Milk Colony, 14 enthusiasts came together to maintain cameras after the Forest Department concluded a camera trapping initiative in the area. Following a leopard attack in 2017, these camera trap images helped the Forest Department identify the leopard in question. The picture that these cameras caught was not scientific, but it helped keep the Colony safe.

The Alley Cat, Leopard in Aarey Milk Colony. Photograph by Nayan Khanolkar, captured with a camera trap.

Camera trap images are not wildlife photography, but there is still heart and emotion tied to these pictures, which are photographed over several months in rough weather and dangerous terrains. Through their unpredictable nature, much like the very subjects they seek to capture, camera trap images take us back to a time when photographs were not easy to take; when errors weighed heavily; when captured images encompassed in their 2D confines a wealth of information; and when the sheer number of images didn’t just saturate our mindspace, but brought with it a sense of validation and purpose.

Share