Beyond the Filter

Can art emerge out of darkness, without the crutch of light? We walk across the boundaries of what we consider ‘civilised’ to what we brand ‘demonic’ and find that art is truly a label-less colour

Praveena Shivram

The Instagram video chat option offers you a plethora of filters to choose from. You can multiply your face, you can expand the size of your eyes and mouth, you can have hearts flutter out of your head, or wear an astronaut’s suit and speak from the moon’s rocky surface. Momentarily, it gives you access to an escape hatch, one that you only need to click to leave the dreariness of the everyday behind and catapult yourself into the quirky unexpectedness of the space behind the screen, into that which is transient in nature but solid in presence.

I would imagine that that is what art is to an artist’s mind – a portal into another, more agreeable dimension, where one is never sure who is bending to whose will and whims, where a brush stroke is one more way to rewrite the rules, to redraw the boundaries. And it doesn’t really matter if you are a banker (not our concern here) or a serial killer (completely our concern here). Art is an endlessly resurfacing filter of the mind.

“There are no rights and wrongs, only ises. Whatever life is, it is. Right and wrong got nothing to do with it”

– Charles Manson, Mindhunter, Season 2, Episode 5

The term ‘serial killer’ was first coined by two agents, Holden Ford and Bill Tench, working in the Behavioural Science Unit at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Academy in Quantico, along with psychologist Wendy Carr. I have this in good authority. No, not Wikipedia. From Netflix, the new-age Wikipedia that endlessly entertains said filters of the mind with shows based on reality. Don’t ask me which one. Reality, I mean, not the show.

This one is called ‘Mindhunter’ and it follows the journey of Ford and Tench as they interview serial killers in prison, to understand the psychology behind the crime to predict and apprehend any future killings. It’s a fascinating quicksand of experience pulling you in, like a voyeur who cannot look away – who will not look away – because this darkness is too appealing. To hear the likes of Ed Kemper talk methodically about how he would cut up body parts and then use the decapitated parts for sexual pleasure, while the agents and Kemper sit within an antiseptic room in prison, sharing slices of pizza and cups of coffee, punctuated by the loud clangs of gates closing somewhere, with us sitting in our own antiseptic isolated rooms witnessing this conversation, that is real and yet unreal… it felt very close to instinctively picking up the mobile phone to record an accident or a road-side scuffle from a distance, engendering the false hope that a recording of this moment was imperative, that somehow justice would be served. And then adding filters and forwarding it on WhatsApp. Because some entertainment never hurt anyone. I watched both seasons of the Mindhunter in a blur of the gruesome inhabiting my space. And I confess, I couldn’t get enough.

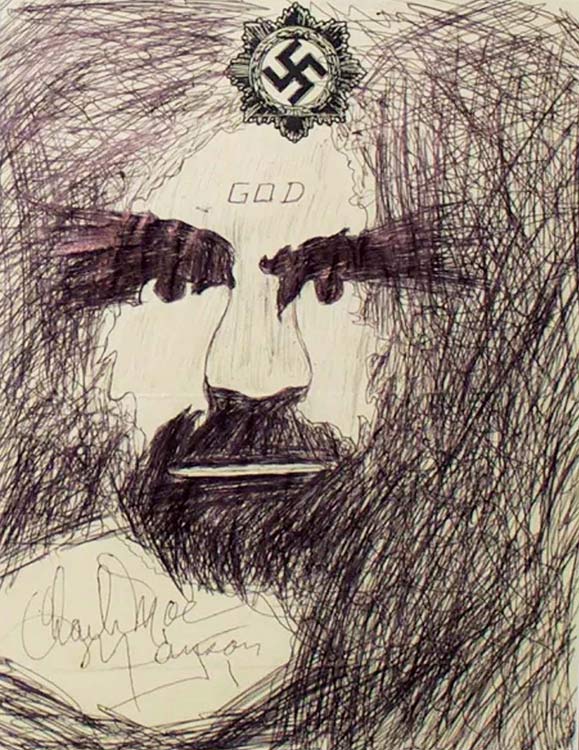

Much like those who couldn’t get enough of Charles Manson, the killer who is said to have instigated a series of killings in 1969, Los Angeles. Two years after his death, the Lethal Amounts Gallery in LA hosted an exhibition of Manson’s paintings, along with other art and artifacts connected to the murders, to coincide with Tarantino’s hit film, ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ that was set in the summer of those killings. Manson is set to have influenced regular, middle-class, white young people to randomly kill seven people. His artwork, though, is not so random. In one of his drawings, a supposed self-portrait, the lines crowding around the face like a child unable to stay within the lines (ha), has the word ‘God’ inscribed on his forehead.

Click h͟e͟r͟e͟ to read more.

Share