Remains of the Day

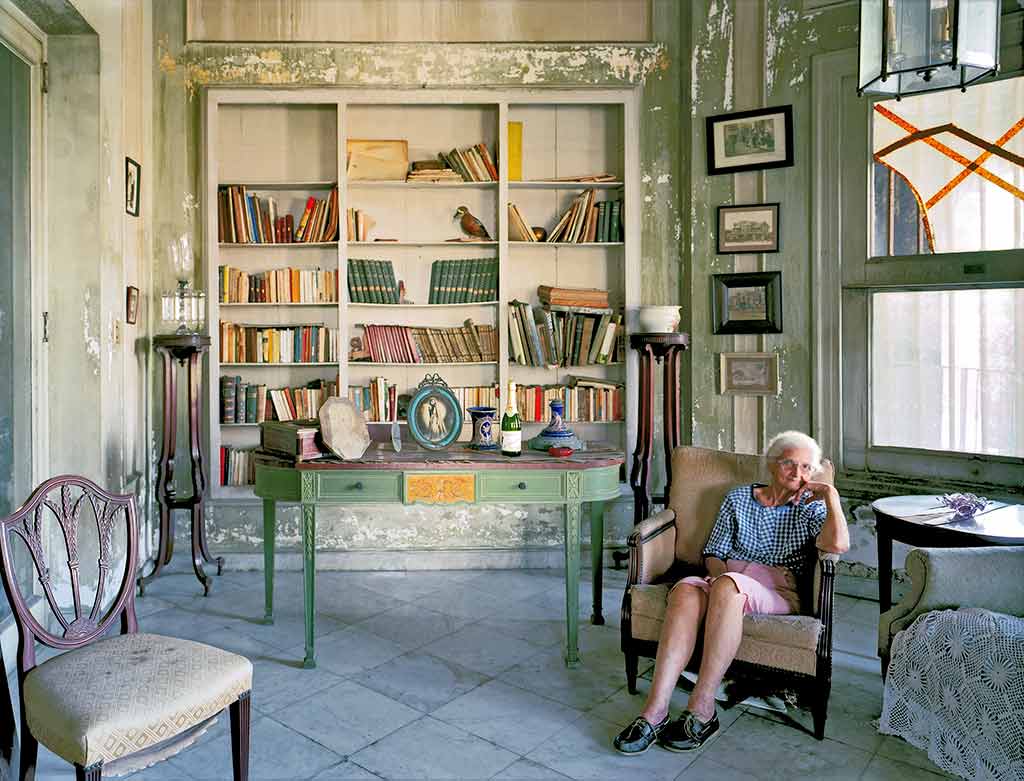

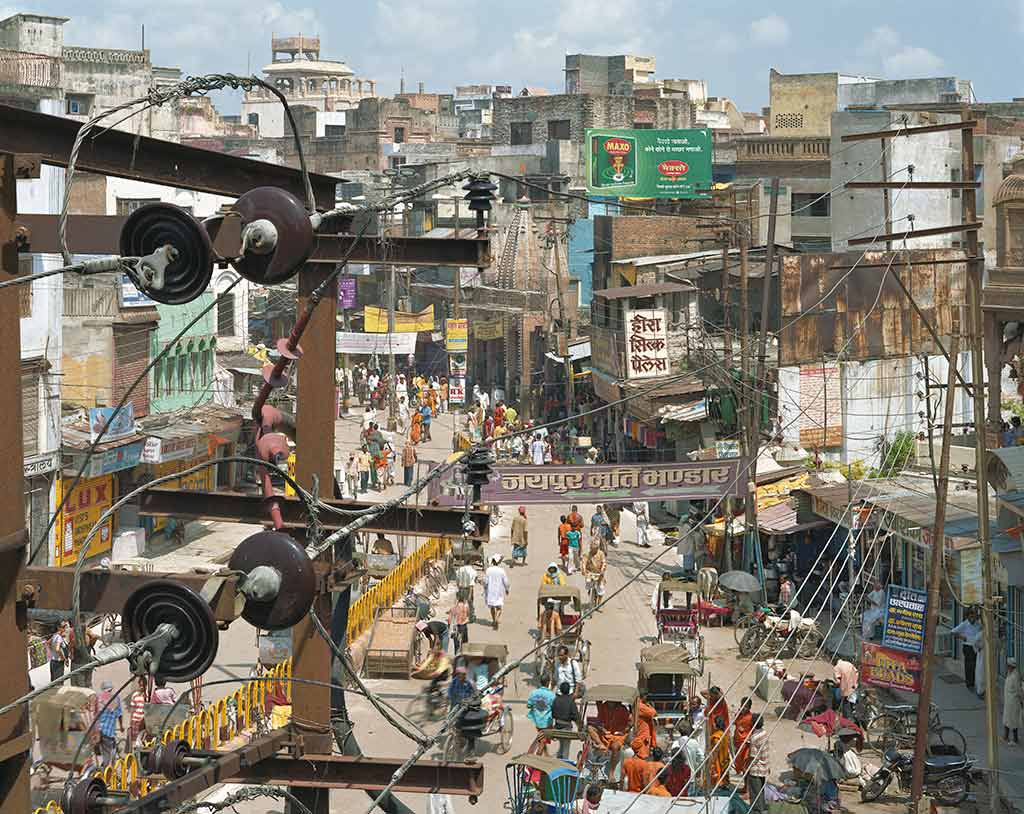

Canadian-American photographer Robert Polidori, known for images that record an imprint of both the past and the present within the confines of a single frame, spoke to us about the cyclical nature of time and the traces of human experiences hidden deep within

Vani Sriranganayaki

I once walked into a room with an alcove that could only be accessed with a trapeze that hung from the ceiling. The room also came with punctured walls patched up with tape, a bunch of expired passports from different countries and half a couch that was propped up with books. Too many questions, I know. I would start with the missing ladder!

It is easily overlooked, as we spend most of our lives walking in and out of them, but rooms often carry stories. They may be made up, like the story of the down-on-his-luck, shady trapeze artist who enjoyed the odd challenge added to his daily routine; but they all carry with them traces of actual lives spent, well, walking in and out of those rooms. For Canadian-American photographer Robert Polidori, those traces hold the key.

Famous for his large-scale colour images of architecture, urban environments and interiors, Polidori creates works that place the temporality of human experiences within the seemingly permanent nature of its surroundings. He does this while rarely ever capturing people. ‘One of the things that I find captivating about photography is how a surface can have many traces of time. I think that the destiny of photography is to trace time. It comes from the nature of the Camera Obscura. It uses the laws of physics to trace the physical resemblances of things. It’s medium-mystic for me. I don’t consider myself a creator. I consider myself a medium. I’m at my best when I am channelling important sites or moments. I let myself be drawn in by signs. So it’s a psychic thing. And I love that. It’s like surfing on time,’ he said over a telephonic conversation where we spoke at length about our capacity to remember and forget, our movements through time and the traces we leave behind in the rooms we inhabit.

Excerpts from the conversation

For a while now, photography has been accepted as the means to document and preserve history. In the current very visual setting, that role encompasses so much more. Now is the generation that forgets often but at the same time remembers vividly. How do you see your practice within this evolving framework?

You know, I say that analogue is made to remember. And digital is made to forget. Because what it means to take a digital photo is not to select something that you hold in value above other things. It’s a check-off list of one less thing that you have to do in your life. To expurgate from the menu of things you have to do. It’s a way to forget. It’s a check-off the list. However, to be fair, it’s also important to have to forget certain things. Because if we were hyperthymesic and everything reminds us of another thing which reminds us of another thing, we cannot go forward in time. So I would say, analogue is made for creation, digital is made for duplication. The digital original is already a kind of a copy. What I feel also, from a generational point of view, is that the digital is good for rapidity, but it makes everything the same. Digital does not favour originality. It favours conventionality.

In a 2007 interview, you spoke about your thoughts on rooms, time and memory and how they prompted your shift from film to photography. Over a decade since, how has that understanding changed, if at all?

No, it hasn’t changed. My fascination with rooms is more psychological and psychic. And I think that one of the things that I realised back then is that because of the physical way that analogue cinema was encoded, when you take a still image with motion picture film, it sort of vibrates. It doesn’t have that eternal stillness that photography has. What drew me to rooms didn’t have anything to do with technology though. It had to do with the psychological aspects of rooms and ancient Western mnemonic memory systems which are based on memorising rooms. Like with the students of Pythagoras – when Pythagoras had to go from Greece to Sicily, they were not allowed to speak for two years and had to memorise empty rooms. If you ever read this book called The Art of Memory by Frances Yates, there is more about it in there.

I read that you first went around the world photographing inner-city habitats in early 2000s; and then went back to most of the same sites again recently. What was that experience like – revisiting and once again looking at the same places and scenes through your camera?

There’s a saying about how the criminal goes back to the scene of crime. That interests me because there’s a Western myth of the perpetual return – how you can keep a moment living forever. When I go back, of course, some things have changed and other things have not; and this fascinates me because it turns a site into an altar. So that’s why I do it. And also, because, personally, I am afraid of death and this is one way that I try to keep on living in this life.

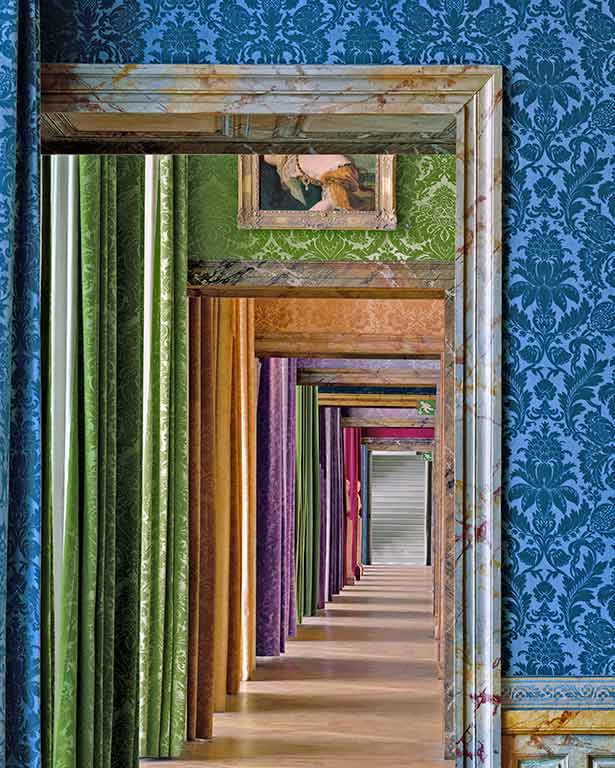

With Versailles you had the unique opportunity of witnessing and documenting the transformation it underwent over the span of 30-odd years. How did you navigate that terrain and what was your primary concern when photographing it?

When I started I had no idea what I was looking at. But over time I became conscious of it. It was an illustration of photographing historical revisionism as seen through museum restoration. Versailles was a seat of government for at least two-and-a-half centuries and the Chateau itself went through numerous transformations. So historians had their choice of restoring it to a particular era. It’s a way of a collective super-ego choosing the point in the past that most pleases them now. Time is cyclic and so are our historical likes and dislikes. That’s what interests me about it.

Photography in the wake of devastation often ends up underlying the loss and destruction – bringing it closer to home for folks who evaded it, and tethering it more permanently to the memories of those who survived it. Can you tell us about your experience of it? What was the pull, with New Orleans or Chernobyl or Beirut?

Let’s start with Beirut. I went to Beirut in 1991 right after the war. Frankly speaking, I forgot why I went. Probably because in my earlier life in America, I was a draft dodger and I probably felt some sort of pain or guilt. I went to photograph what I would call the aftermath of war. It was a convenient place for me to go. What I was interested in is that after the war, the people there wanted to save parts of the city the way they were because they said they’re like wrinkles on our skin. We earned them. Chernobyl was more like a modern-day Pompeii. And New Orleans, well, actually I had lived in New Orleans as a teenager. I went to high school there and I had lived through Hurricane Betsy. But the amazing thing about Hurricane Katrina was that the cadavers there were quite fresh. And the houses were like discarded exoskeletons of life. Yes, over 2,000 people died. But almost two million lived. And they had to go live another life someplace else. It’s like being a refugee in your own home.

This is also an interesting question because in the Anglo-Saxon world, let’s say in the United States, Canada or Australia, my work is criticised for being ‘ruin porn’. I don’t get this in other cultures. When they say: ‘That’s pathetic!’ it means it’s below something worthy. But the word pathetic – ‘pathos’ – comes from Greek, meaning having empathy and sympathy. For the Greeks, only three things – Pathos (death), Ethos (godly concepts) and Eros (eroticism) – were worth illustrating in art. For some reason in the Anglo-Saxon world, pathos is not worthy; because they want to stay young forever or they are denying death in some way. To me, that is just not possible.

And, finally, what do you personally look for in an image when capturing it?

It’s really the Camera Obscura that captures the moment. Film only records it, digital only records it. The film is not the magic instrument. It’s the Oculus. Where you point the camera is the question. The picture that you get is the answer to be deciphered. Like with the oracle at Delphi – a person would come and ask her a question on a piece of paper. She would read it and then being inebriated by the gases that are coming up from the deep well of a chasm, she would say some words that would only have meaning to the person asking the question. It’s a psychic thing. So what do I personally look for in an image when capturing it? I’m looking for the subject to reveal itself. I’m not interested in what I think about a subject; I’m interested about what a subject feels or thinks about itself. This is what mediums do. Mediums aren’t there to give you their opinion. They’re there to reveal the nature of the subject.

Robert Polidori on his recent work at AlUla.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

All Images Courtesy of Robert Polidori.

Share