Walking into the Unknown

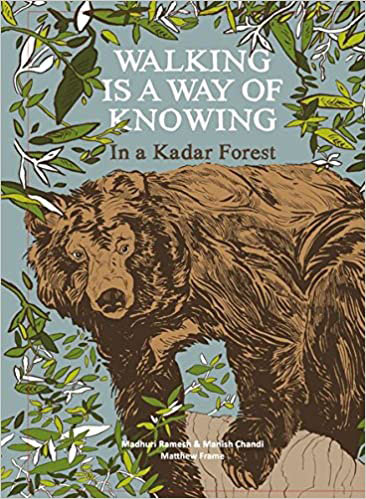

Tara Books’ ‘Walking is a Way of Knowing in a Kadar Forest’ written by Manish Chandi and Madhuri Ramesh, and illustrated by Matthew Frame, is a vivid sensory experience and a subtle journey of discovery

Praveena Shivram

ISBN-13: 978-9383145607.

‘Paths have character: there are easy ones, challenging ones, unforgiving ones, ones that encourage you to walk with a steady swinging rhythm and others that tease your stride with odd twists and turns.’

A year ago, I received this book as a gift. And because every book has a very specific time in which it has to be read, and a very specific path it takes to your heart and soul – sometimes challenging, sometimes unforgiving, sometimes encouraging, as Madiyappan from the Kadar Forest might say – this one languished on my bookshelf till the arrival of a virus and a lockdown. And because walking now meant incessant rounds on a terrace, this book particularly called out to me.

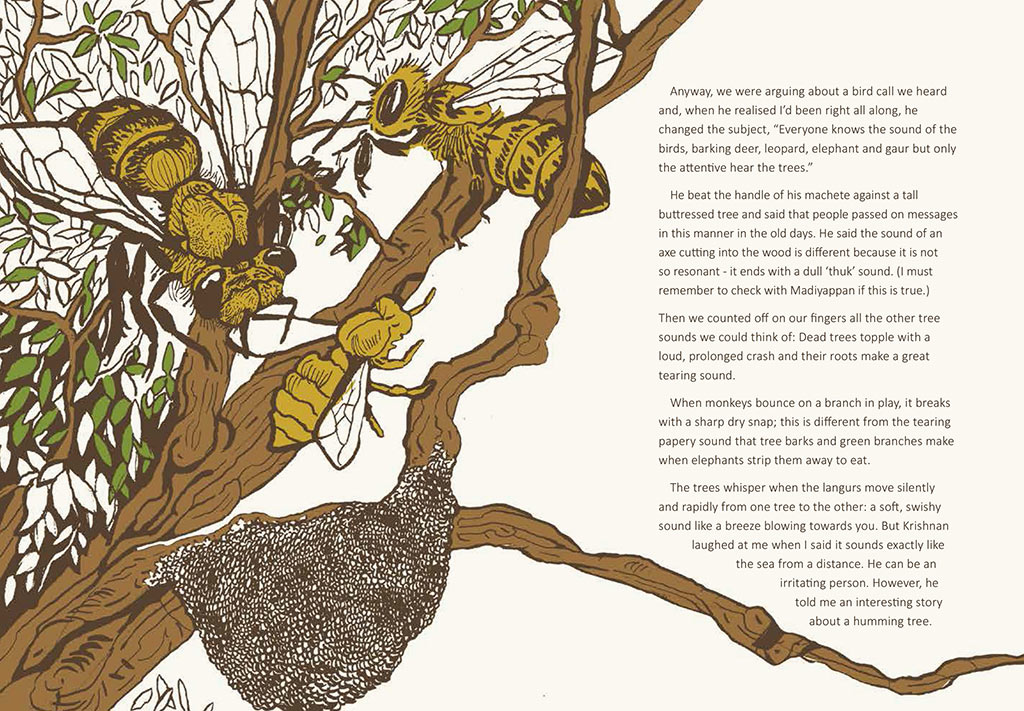

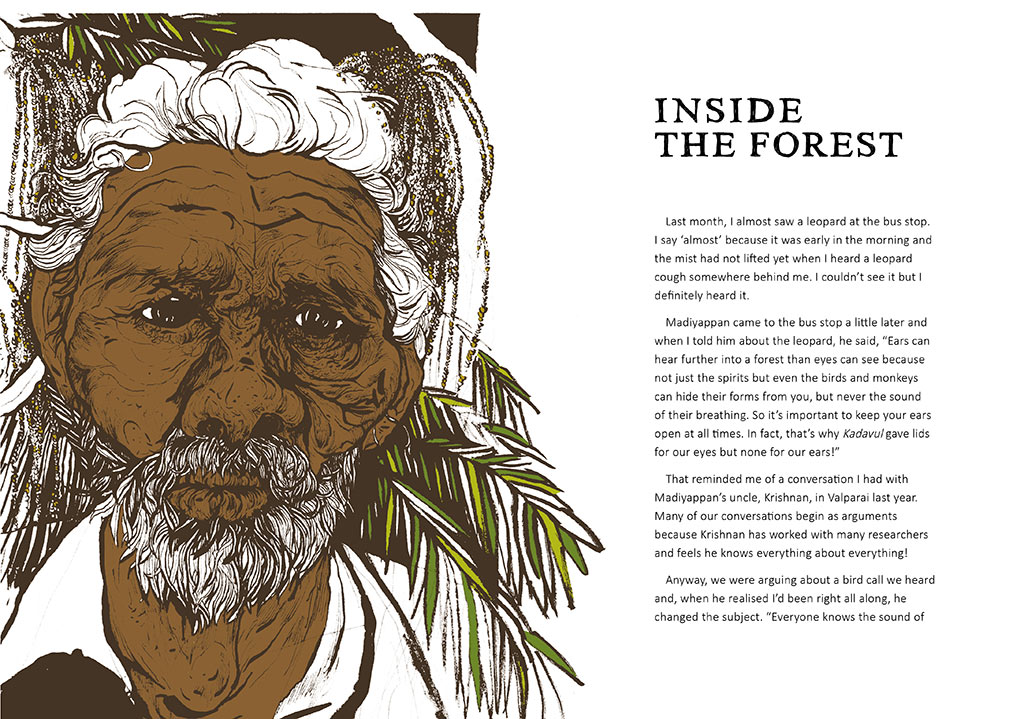

It’s a thin book, without page numbers, printed in a font that is easy on the eye, with illustrations that often burst out of the page in muted colours of green and brown, and you will end up finishing it in less than an hour. But you already know when you walk the forest with Madiyappan and Padma and Shanti and Krishnan, and listen to the sounds of the birds and beasts, and the smell of poop (yes, yes, don’t cringe), and the taste of honey and jack fruit curry, and the touch of our feet on the ground, on leaves and mud and twigs, you already know this isn’t that kind of book you read once, tick off a box, and keep aside. You know, like the pull of rain to the earth, you will keep going back to this book, to its pages of unhurried comfort and deep wisdom, to the wrinkles that reside on faces like crevices on mountains, to the words that meander into our minds like roots. You know this book is going to grow old with you.

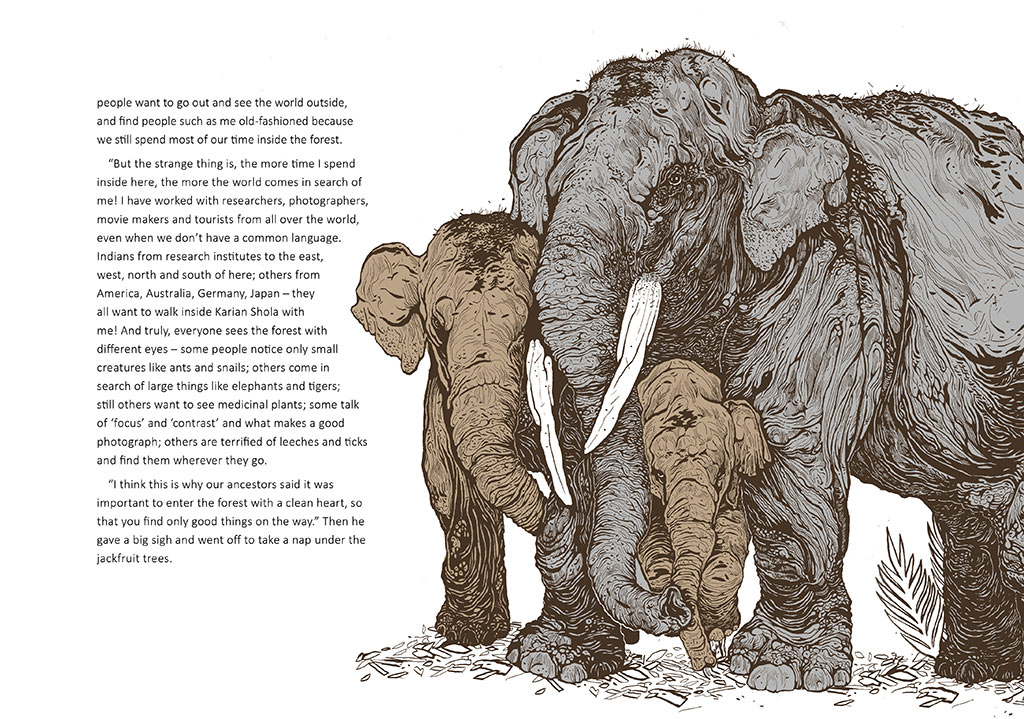

On the surface, the book is about the writers’ journey (where the two become one, automatically universalising the experience) into the forest with the Kadars, a ‘forest dwelling tribe of the Anamalai Hills in south India’. It is an outsider’s perspective on life in the forest, on understanding the many temperaments and moods of the forest, on the dynamism of the balance between what she chooses to reveal and keep hidden, on making a home where the boundaries are liberating and not limiting like walls. But as you peel the layers, you realise the book is almost a philosophical lament of a time lost in the glare of city lights, of an ideology that is intertwined with nature’s intangible ethos that can only be a lived experience, and of a day filled with moments of simplicity and togetherness, something only a forced isolation can bring to us today. This, to me, is the triumph of the writing, that I can sense the unconscious and make it my own, knowing fully well that when I make it my own again, at some other point in time, the meanings will change. And knowing then, like I do now, that the Kadars looking out at me from the page with their unwavering gaze (the triumph of the illustration) are not flat, two-dimensional beings, but living, breathing entities who can truly see me.

‘We return to the forest again and again and again: as much to fill our stomachs as our hearts. The first time a man climbs to get honey at night remains etched in his memory; the adventures we share with our companions keep us and our grandchildren entertained through many monsoons; the dullest day is enlivened by spotting a bird or an animal; and our spirits rise when we walk trails that take us past trees that know our ancestor.”

Share

All of 85 summers I went back