Short Shorts

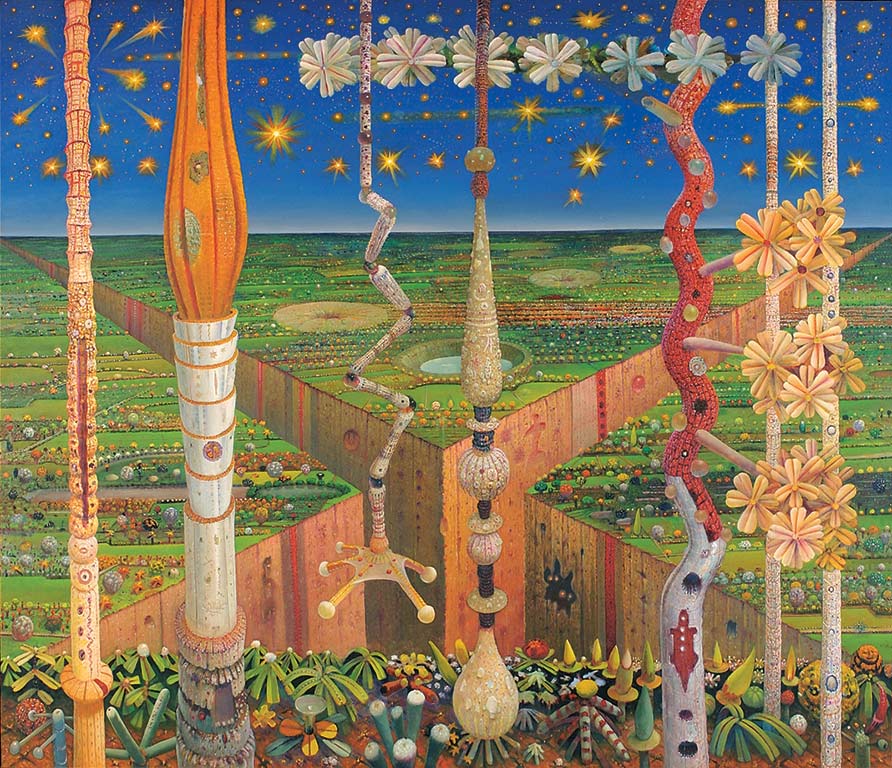

Arts Illustrated’s micro-fiction series borrows from the thousand words through which a picture speaks to create a moment of experiential art. Featured here is one such piece based on works created by artist Jyothi Basu

Manoj Nair

A Separation

He was afraid of closing his eyes every time he went to sleep. If he did that, he feared, he might die in his dreams. In his dreams too he had been sleeping alone. He was lying precariously at the very edge of the ledge of memory, of the tiny space available to him on the shared mattress. His body couldn’t help it: all those years of sharing a bed had twisted his mind and left on it seemingly irremissible warts and wherever he begins, he returns, mothlike, to the edge during the night. And, of course, the free fall! He had lobbed a grenade into his life, and thought everything would be different, but it was not. He remembers leaving everything to make a fresh start and looking for a spotless perch to sit on.

After all, it was a new beginning and it had its obvious promises and incandescent charm. His muscles stretched in a smile that he felt in his veins. He had made a firm resolve to transform from what he had become over those years: passive, suspicious, withdrawn and lazy. But he has now resolved to emerge from the clutches of the cramped cocoon of his relationship to become a beautiful butterfly admiring the wings that are meant for him. Separation was not a garden of dreams. But it held the promise of an Eden. He now lies on the ledge, not to be separated from the colours behind him, waiting for them to turn soft and silken in the moonlight.

The Wounded Hill

The two had fled their homes into the unknown. One was a polite assassin and the other a gun dealer. The dealer was tall and had a cold expression on his face as if he had just returned from a drink with Mr. Death. The assassin was short and had to look quite a way up to meet the eyes of the dealer. But nothing in his gait hid the fact that he was cold-blooded. The fact was they were on the run. They had nowhere left to hide.

‘There is nothing to be done,’ the assassin said to the dealer. ‘No people to be killed.’

‘Well, there is no time on earth that we can wait for,’ the dealer said. ‘I never knew anyone by name. Even when I was a pimp. I knew each one by their face and would tap them or pat them or beat them to call them.’ The assassin looked at him as they climbed the wounded hill. His face sporting a smile that didn’t seem to mean anything. They had to go over the hill to the other side before darkness craved their mind. They were crossing over to a foreign land, a few miles from the sun, where reaping time had come.

‘The women were never more than merchandise for me,’ he continued. ‘Just as the armoury were later.’

He went on bragging about his spoils till they reached the bottom of the hill. They were just a few miles from the sun. But there was a problem. They had to get past a ravine just about six feet wide, full of all kinds of crawling creatures. They looked at each other. The dealer knew he could jump across, but the assassin had doubts in his mind. The assassin smiled at the dealer when he looked at him questioningly. This time with purpose as if assuring him that he would make it. Then he took out a nail from his pocket and jumped up and drove it deep into the neck of the dealer. The dealer fell across the ravine clutching his bleeding neck. As the assassin walked over the bridge formed by the body of the dealer he thought, ‘After all, there was still one more to be killed.’

No Dreams for Children

When Ibrahim and Salem lay down on their twin bed, they wanted to dream the same dreams. Together. They wished they could pull the blanket of clouds they saw each evening in folds over each other. One of the dreams they wished to see was to be able to dive together into the depths of the sea and make friends with all the talking fishes they had seen in an English film. Ibrahim was particularly fond of one fish called Dory. He thought he could be by her side as she suffered from extremely short memory. Every day they would sit by the rock up the hill and wonder what all those short trucks with long noses were trudging through their neighbourhood kicking up dust and blinding them. It was the rock they found for themselves ever since their mother had agreed that they were big enough to go out on their own. Salem, the more voracious reader of the two, asked: ‘Are they all liars like Pinocchio?’ Ibrahim shook his head as he waved the dust ball away with his hands.

That night when they lay down to sleep they held each other’s hands determined to dream that dream of all dreams together. They closed their eyes and saw a planet full of strange things. It looked like everything had come crashing down. They were on either side of the planet. A river ran through it dividing their joy of togetherness. The sea was in the distant crimson horizon. Late in the night Salem heard something fall with a bang in their house. Not until the next morning, when he woke up amidst the rubble around him to see people wrap Ibrahim and his parents in black sheets, did he realise that the dream had been destroyed.

The Tree

It is true that he did not own a farm nor did he lose his mother to a tree. His mother had died of cancer when Sanathan was 13. But all the stories of his childhood were told to him by his mother sitting under this tree. How he lost his first tooth; how his brother locked himself up in the loo. The tree was all that he had known about agriculture. It was more like a pet to him. As a child, he always thought if it grew taller it would touch the sky or if it bent sideways it would go past the sea by the side of his house and kiss the horizon. Then he could climb up and sit on its branches and talk to the birds that flew up in the sky and seemed as far away as the airplanes. Or he could graze along and shake hands with the setting sun. He had never seen the birds or the planes on the branches of the tree. How it made him sad and his mother would console him by saying one day you will be flying in one of those machines and can talk to the birds. The tree growing up to the sky was a better option, he thought. He had a fear of flying since he was a child.

When the tree came down, they said that Sanathan was sad. Instead, he was burning with anger. Someone heard him say that he would lift it and hurl it at the sky so it would split the sky wide open and then like a boomerang it would return and tear the earth apart. None knew the truth. Nobody could confirm whether he actually tried to lift the tree or the tree fell on him. What they knew as truth was: when trees die, people die.

Letter to a Friend

Dear Sunil,

How are you? I know that is a stupid question because obviously you are more than happy in your world. Else, you would have spared a thought for me. Maybe in your world you are not allowed to. Down hear it is deeply dark, dreary and depressingly dusty. Every moment when I go about my chores I grudge the day when I turned down your offer to come with you up the ladder. You kept on waiting for me until you were the last one to go up there. After you were gone they pulled the ladder up. I am writing this in the old-fashioned way with the forlorn hope that when I throw this up with all the might I have in my hands that fall from my drooping shoulders, it might reach you and you might drop down a piece of paper with a line or two. E-mail was good as it did not have to deal with physical distances.

But then, when you put your first foot on the ladder, you were bidding adieu to the e-world for a world of ultimate fantasies. Every day I look up hoping that the ladder would come down again like in a trapeze and the routine would be repeated. Maybe I should put this letter in a bottle and throw it up hoping that you chance upon it someday and save me like sailors marooned on an island. Here, if I am not choking with emotions, then I am choking with the lack of breath. There is no oxygen outdoors. So when we step outside we wear masks with cylinders strapped on to our backs. All of us down here have our head and shoulders bent forward and walk with a stoop. So when we have conversations we press Play on the tablet screens fixed to our wrists. Soon we may have to crawl on all fours and converse like animals do. Maybe that would be the day when you would appear at my doorstep with flowers from your land and we would throw them at each other like we used to in our childhood. Please do reply even if I am not there anymore to receive it and you won’t receive this either.

Yours,

Anil

___________________________________________________________________________________

All Images Courtesy of Jyothi Basu and Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke.

Share