Stitch in Time

An idealist’s proposal for sustainable fashion and the ever-pliant, ever-reversible art of mending, and, shall we say, re-imagining

Arti Sandhu

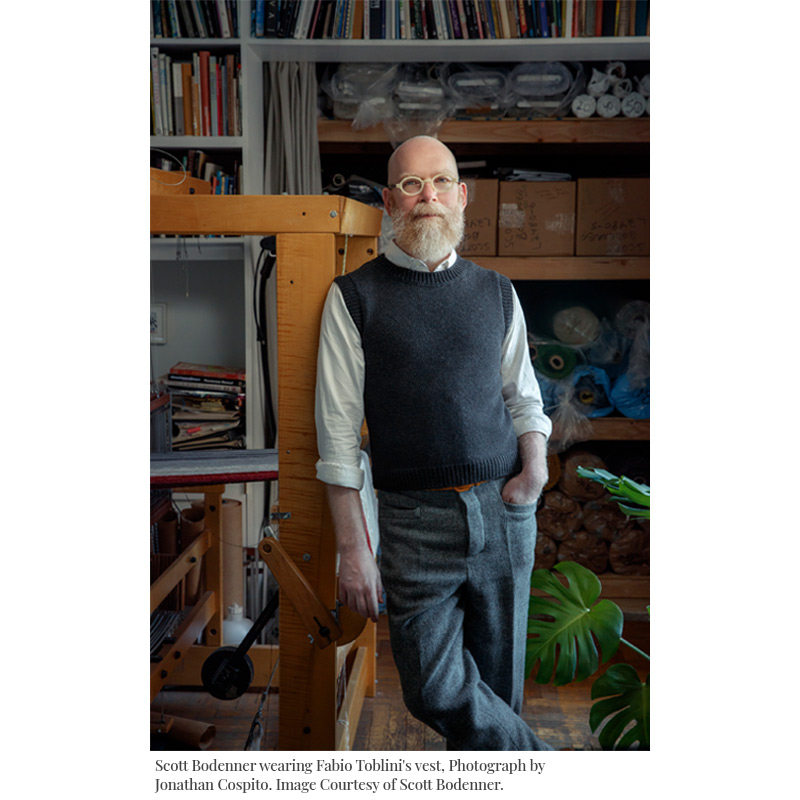

Brooklyn-based textile artist Scott Bodenner writes about a sweater vest his husband knitted for him as part of the FIT Museum’s Wearable Memories online blog series – a crowd-sourced project that was initiated as a compliment to the recent exhibit titled Fashion Unraveled that showcased garments that were either repurposed, mended, deconstructed, or in some cases, unfinished. According to Bodenner, his vest was made from yarn unraveled and re-knitted from what was originally a well-loved cardigan that held a special place in his husband’s heart, making the piece ‘the sweetest love song’.

As the once quiet murmur about sustainable fashion gathers momentum and turns into what is now a loud crescendo informing designer philosophies and brand missions globally, this personal story struck a chord with me. Firstly, because it reminded me of the countless sweaters and warm vests my grandmother knitted (and subsequently re-knitted) for us cousins, made from older out-of-commission sweaters that she carefully unraveled and remade to keep up with our growing bodies. Many of these sweaters were striped. Not because it was a pattern she preferred, but because it was a practical way of reusing limited quantities of yarn and colours. So, when one small ball of reused yarn ran out, she started a new colour, a new stripe.

Besides its personal resonance, the stories of the re-knitted vests also form a critical component of a successful circular economy – one that is restorative, regenerative and where waste has been designed out. In the case of fashion, this can mean designing new products or services with their end use, reuse, or repurpose in mind. Such an approach of design considers much more than the journey up to the point of purchase of a garment, and instead considers its entire trajectory or ways in which its lifecycle (including any waste it creates along the way) can be re-routed or, better still, reversed.

The aim here is to not throw shade at the design and creation of new artifacts, or the remarkable efforts taking place in the arena of sustainable design practice. However, most of the time, we are still expected to buy a product, more importantly, a new product. Even if the intentions of the designer is to create a sustainable garment – one that is well designed, highly crafted, ethically sourced and made, and so on – eventually, through the creation of a new product and without designing into it a mechanism for recycling or repurposing both its production and post-consumer waste, often it too fails to achieve fully the goal of sustainable design. In addition to this, we cannot assume that every item of clothing will be held on to forever. Some clothes simply don’t have the structural integrity to make it past a few washes. (H&M, for example, is noted for intentionally creating garments that are not meant to last beyond eight to nine washes or season of wear.) For those pieces that we could perhaps hold on to for longer, the fashion system has built in the mechanism of planned obsolescence, whereby even if a piece of clothing is presentable, wearable, worth saving, it appears to our eyes worn and unfashionable, unworthy of our patronage. The fast fashion system pioneered by brands like Zara and H&M has further quickened this cycle, as has the global real-time engagement audiences have with runway shows through the Internet. As a result of which the wait for a new trend to kick in (and the old one to bow out) is even lesser. Donating no longer wanted or worn-out pieces of clothing to a good cause or textile recycling units may ease one’s conscious, but it is highly likely it will end up flooding markets elsewhere – markets that are now much less reliant on old hand-me downs.

Again, the intention of this piece is not to say buying or creating new things is wrong; many a livelihood as well as global economies depends on this, but the pace at which we have become accustomed to consuming new things has increased exponentially in the past few decades. To speak of truly sustainable design futures, it is even more imperative now to embrace as close as possible to a circular model of economy, as opposed to the linear model we currently have. One that attempts to complete the cycle or close the loop by building in mechanisms for reuse, recycling, re-routing waste.

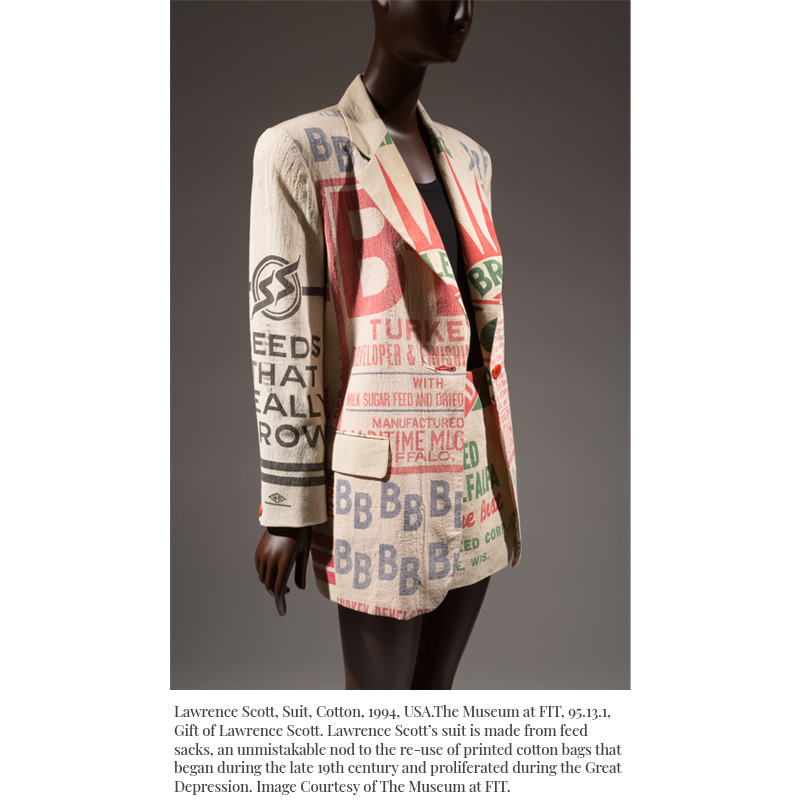

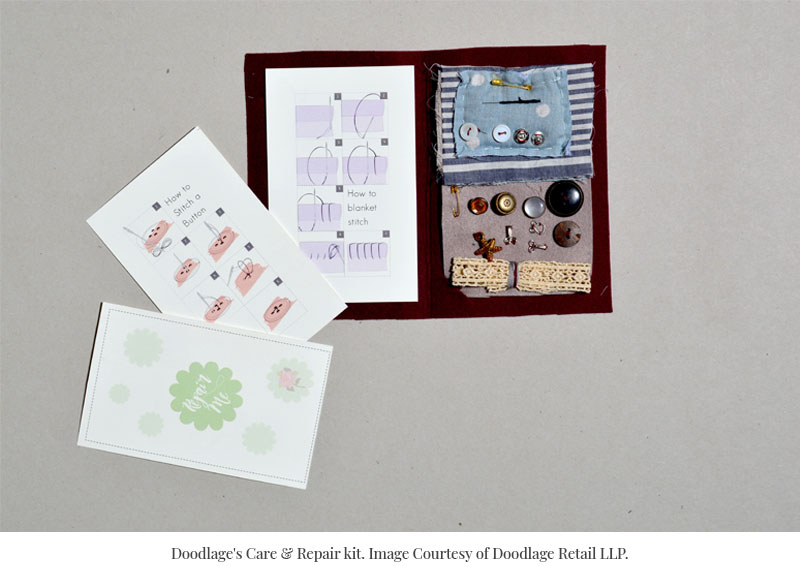

At first this seems like an unimaginable concept. However, here lies an opening for proposing a variety of experimental, risky, ideological frameworks that could perhaps one day become feasible (much in the way fast fashion was once an unimaginable concept). Interestingly, many of these ideological concepts are not wholly unfathomable, as sustainability is already embedded in the DNA of our craft practices and older traditional frameworks. Yet, many of the circular fashion strategies rely on the designer or producer to take the first step or make the change – zero-waste pattern-cutting, production waste recycling, water purification, and so on. What can consumers do from their end to help achieve the circularity I have mentioned? I believe age-old techniques of mending, darning, patchwork, or rafoo could be one answer to this. Techniques that were once a key factor for ensuring the longevity of not only special clothing, but also basic clothing items like socks (the darning of which was my grandfather’s lifelong pursuit).

I hear you thinking, ‘How can we possibly convince today’s time-poor fashion consumers to mend their clothes? Especially when there is so much novelty (affordable too) out there?’

Much like the way new trends re-appropriate past trends in fresh ways, innovative design solutions that build on the past always do so in ways that are both familiar and yet novel so they remain relevant to current times. This makes it possible to consider alternate ways for viewing the act of mending. One that goes beyond reversing the life of the garment or the hole that is being mended, to enhancing or evolving its design and make up in such a way that it could function as a new piece. Mending that instead of hiding behind the scenes or seams, quietly holding your clothes together, now screams loudly of its existence, and parades its designs, colours and disregard for the notion of blending in. Placing embroidered bugs where holes once were, felting coloured wool into moth-eaten sweaters, selecting colours at random when fixing prized Jamawars, patching or layering scraps to create new textiles, or applying diverse hand and machine embroidery techniques as part of the mending. The possibilities are endless. In this way, the art of ‘visible mending’ could not only help mend garments, but also the fashion cycle.

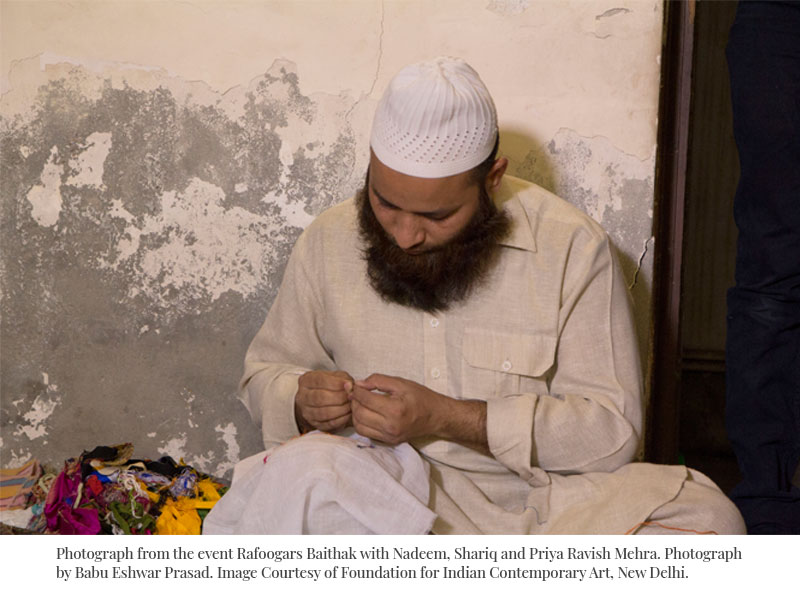

While I was in Delhi recently, I decided to pick up on a thread I had started years ago of learning basic rafoogari or darning at our local drycleaners in GuruNanak Market. Back then, I would meet their then rafoogar and sit and watch him mend clothing in an attempt to learn from his examples. I was delighted by the way in which he could read clothes, read holes, and read people while fixing their follies. Now, almost two decades later, Mohammad Shariq visits the same dry-cleaning shop on his weekly rounds to gather up mending orders from around Delhi. We chat about this lost art as he fixes the most ordinary black sweatshirt hoodie and a striped polo t-shirt. I am amazed that people still send such clothes out to mend. Clothes that are now so cheap to replace.

Mohammad is also one of the few select rafoogarhs who worked with Priya Ravish Mehra – the Delhi-based textile artist who promoted the art of visible mending through commissioned pieces and live exhibitions of rafoogari. As part of her life long research into preserving this craft as well in her own art practice, Priya encouraged rafoogarhs to create pieces that made the invisible visible, and highlighted their darning techniques and their potential as a metaphor and solution for life’s unpredictable cycle. One of her last exhibitions was a performative piece – a Rafoogarhs’ Baithak at the India International Centre in collaboration with the Craft Revival Trust to demystify this art form. While Priya sadly passed away a few weeks after the exhibition, her ideas continue to inspire. I felt privileged to have met such a distinguished rafoogar as Mohammad Shariq – and came away excited to relearn those time-tested techniques so I too can close the loop and fix a pair of old merino socks that lie unused at the bottom of my wardrobe – but this time with a riot of colours.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

With Special Thanks to Mohammad Shariq. For more information call 8287015929 and 9058837146.

Share