The Sonic Waxing and Waning of A Quiet Place

Sound, in the film ‘A Quiet Place’, becomes its own character, embodying tension, emotions and a terrifying way of living – one that makes you ‘hear’ the film in your very bones.

Godhashri Srinivasan

When you step into an anechoic chamber – a room that absorbs all sound – there’s a ringing in your ears. And when, your ears open up, you hear things you never heard before – you hear your heart beating, your blood as it rushes through your veins, your lungs, expanding and contracting with every breath. When you move, you hear your bones grind, and your muscles stretch. You lose your balance, because the human mind uses sound cues to orient the body.

That is what it felt like, watching A Quiet Place – an effect carefully programmed by the film’s sound designers Erik Aadahl and Ethan Van Der Ryn. A Quiet Place follows a family living in a post-apocalyptic world where monsters with highly sensitive hearing hunt down anything that makes even the slightest sound. Sound, in the film, becomes its own character, embodying tension, emotions and a terrifying way of living – one that makes you ‘hear’ the film in your very bones.

Sound, as proven by every horror movie ever made, plays an important role in escalating tension. But A Quiet Place turns that on its head and places the tension solely on the absence of sound. ‘It’s inverting that whole concept, where it’s more about the negative space, the quiets, and the shades of quietness, and ultimately, the silence. Where then, when you do play a sound, you’re naked. So, it has to be perfect,’ said Aadahl in a conversation with The Verge.

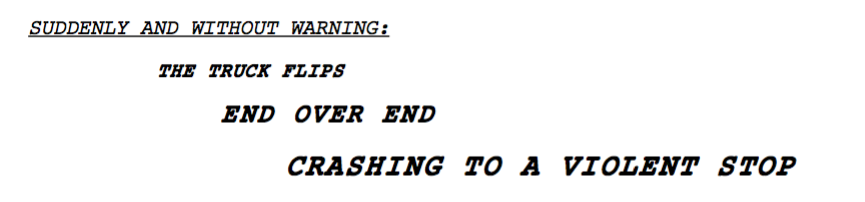

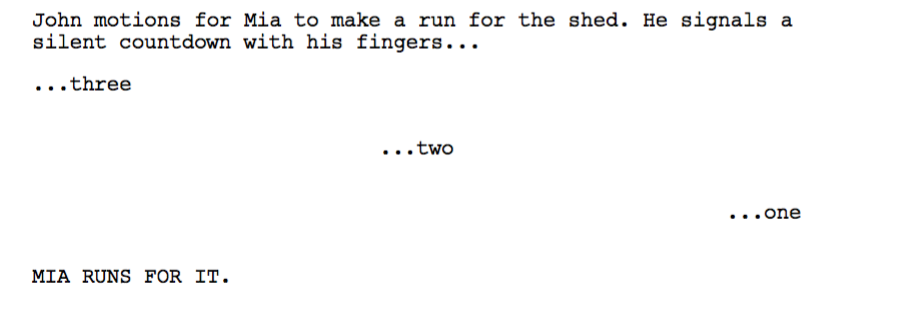

A Quiet Place writes sound ‘into its DNA’, starting from the unique formatting of the script, which plays with font sizes, block letters, one-word pages, drawings and maps. A progressively decreasing font size or underlined and bold words play with the ‘loudness’ of your ‘thoughts’.

The film continues the experimentation with sound design by using sound to understand characters. In a movie where there’s less spoken dialogue, Reagan, 8, who is deaf, interacts with sound in intimate, painful ways. Her deafness becomes a source of guilt after her little brother’s death, when she hands him a toy that emits a sound she cannot hear. She feels like dead weight, endangering the rest of her family. With frustration, she attempts to adjust to a new implant her father makes for her, which does not work no matter how many times she snaps her fingers near her ears. The unyielding silence remains a taunting blindfold.

When everything is stifled, screaming becomes a strange outlet – for pain, bottled emotions and love. When father and son visit a waterfall or talk for the first time in the film, the sound of the waterfall masks smaller sounds. Father and son yell against the cascading waterfall. The action – yelling – is simple, but the visceral sound of it, detached from an otherwise muffled, whispery world means freedom.

There is no natural place on earth with zero sounds. We are not aware of the layers of sound we constantly hear; at least not until they stop. The horror of complete silence is so unnerving because complete silence is not natural. It triggers some deep-buried fear and anticipation. While humans associate high-frequency sounds with danger, the stripping of sound makes this danger omnipresent.

When placed against this muffling, every sound attains an eerie significance. In silence, every sound becomes an explosion, a weapon and a diversion. In the face of absolute silence, who wouldn’t yell at the top of their lungs if it meant salvation?

Share