A Hat (Ahem, Fedora) Tip

Waswo X. Waswo spoke to us about ‘The Intruder’ – his latest series of interventions on hand-tinted lithographs from George Francklin Atkinson’s ‘Curry on Rice’

Vani Sriranganayaki

In 1860, just a few years after the Sepoy mutiny that sparked the Indian independence struggle, George Francklin Atkinson released a series of coloured prints titled Curry and Rice on Forty Plates or The Ingredients of Social Life at Our Station in India. In the wake of the Sepoy mutiny, Indians were seen as uncivilised and treacherous and the British colonialists were under added pressure to distance themselves and ascertain their British-ness.

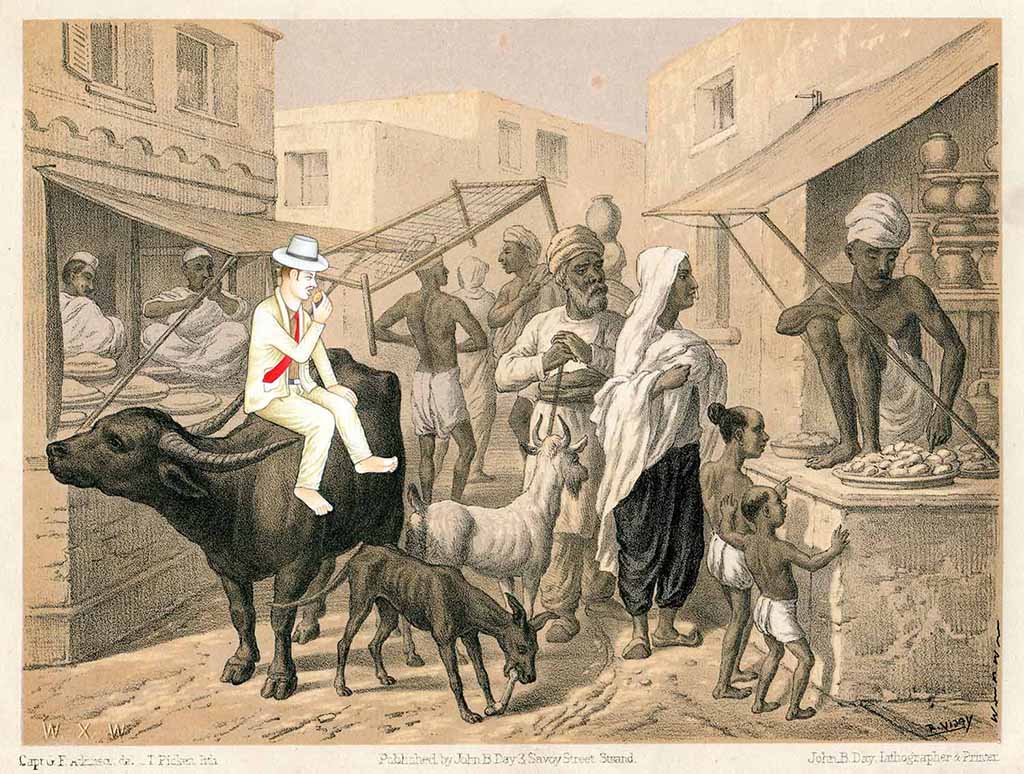

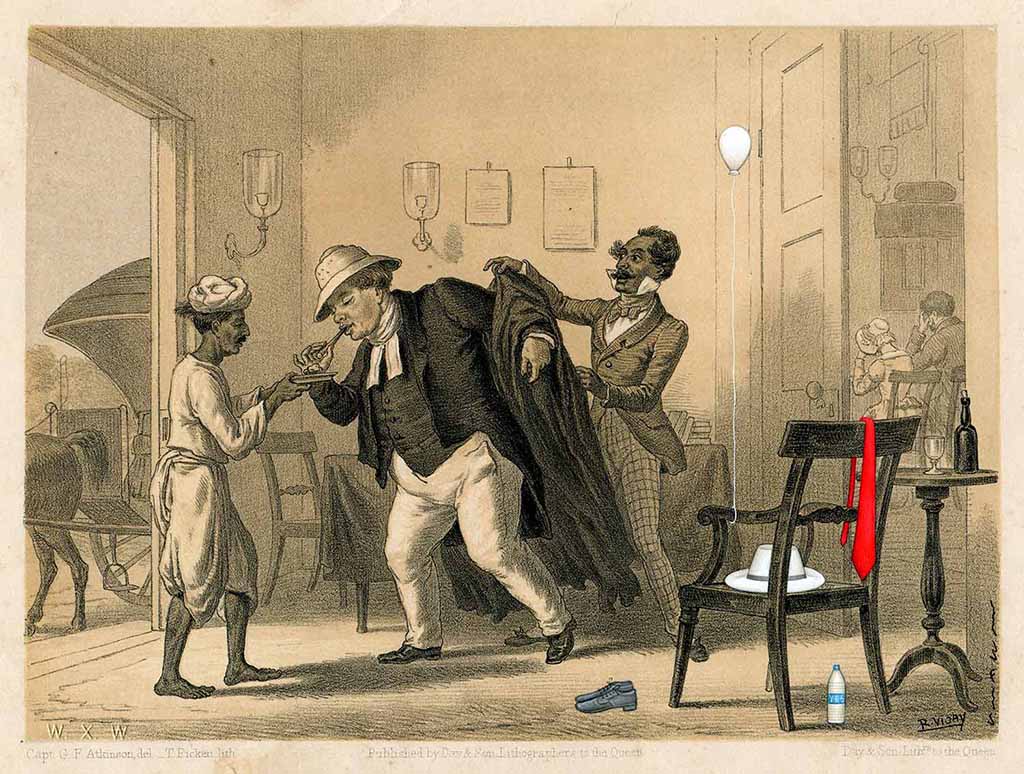

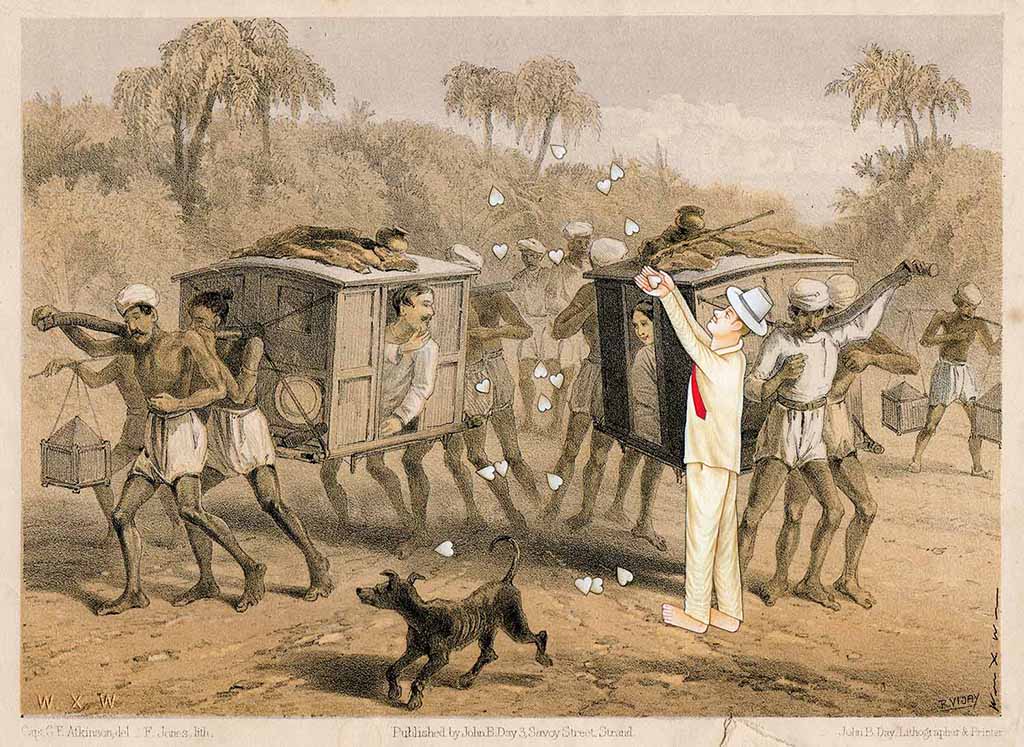

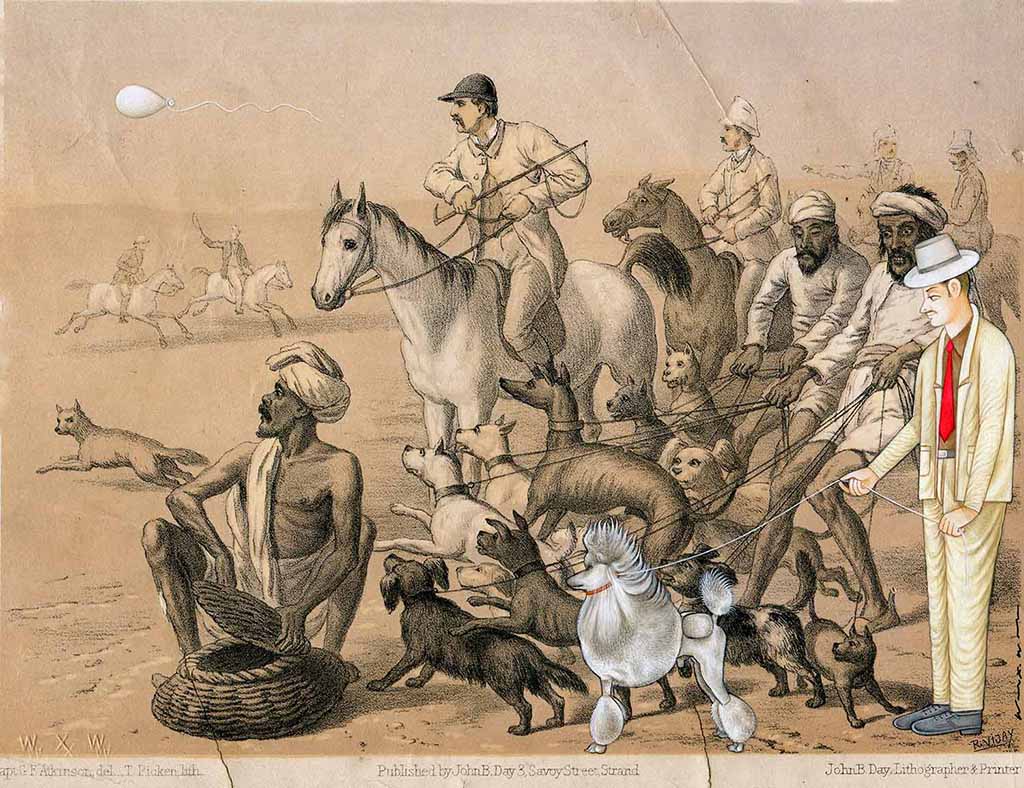

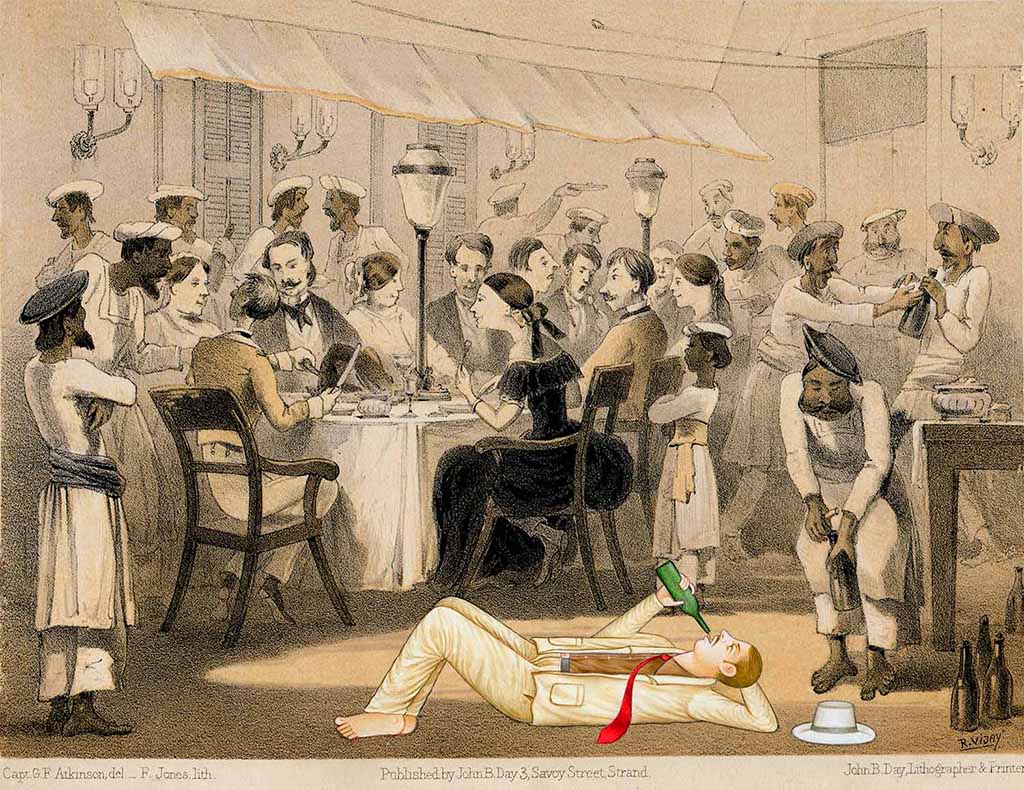

So for Atkinson to put out a work critiquing the lives and behaviours of the British in 1800s India in itself was an act of subversion. But with Curry and Rice, he went a step further and used the fictional town of Kabob to shed light on the underlying tension that dictated the relationship Britishers had with their colonial subjects – all in a humorous way. If you are wondering as to why we are rehashing this now, it is because acclaimed artist, photographer and writer Waswo X. Waswo recently brought this 160-year-old nugget from history back into contemporary cultural reflection with The Intruder – his latest series of works, along with his long-time collaborator R. Vijay, where he intervenes into Atkinson’s narrative with, you guessed it, the fedora man! ‘So, our fedora man enters Atkinson’s world to both mirror his works and alter them. He might fit in, in terms of complexion and costume, but he subverts the image with his genteel, well-groomed, and stereotypically gay poodle held daintily on a leash’, said Waswo over and e-mail where we spoke about the project and his experience of travelling visually through time.

Excerpts from the interview

What about Atkinson’s work drew you first? Why did you decide to work on his representation of India?

I had never looked at Atkinson’s work closely until the day my friend Kusum in Mumbai messaged to say that she had a few vintage Curry and Rice prints in her collection and wondered if I had any interest in buying them. These prints had been in her family for a few generations. When I saw them, I detected something familiar about them. Kusum had only five of these prints, but they were enough to give me the feeling that Atkinson was making a satire on Indian/Colonialist interrelations. Soon after, I bought a large number of original Atkinson prints from my friend and dealer Hemant in Udaipur. I’ve of course been playing with the figure of the ‘fedora man’ in the miniature paintings that I do with R. Vijay for years. But it seemed to me that it was time for the fedora man to do a bit of time travel, and enter the world of Atkinson’s satirical town of Kabob, as both a spectator and a participant.

The new series takes on questions of evolving identities. That certainly is not new to you. But it also takes on questions of history – both political and personal. How do you navigate this – especially at a time when veracity of history is often questioned?

I can be quite political in my opinions, and I’m not afraid to express them, but when it comes to my art I’ve always tried to focus on the human element; the narratives of human interactions on personal levels. History, of course, will always form a portion of the backdrop against which these interactions take place, and perhaps more so in this new series of interventions than in our previous works, where narratives and symbolisms often play upon the stage of a lush natural environment. In my previous works done with R. Vijay I could argue that the focus was upon the common man, who is often not as aware or concerned with histories and politics as are academics and art critics. It is more difficult to claim this now with The Intruder walking into Curry and Rice. But I still tend to see him as the eternal outsider, just as uncomfortably clueless with the British colonialists as he might be in an Indian village.

In your works, the man with the fedora is visualised as the ‘silly man’. In Western popular culture, it is still a characteristic appropriated to Indian characters – what with the tired trope of head shaking and cow worshipping. Why is your appropriation so vital to your art?

I’ve always wanted the fedora man to be a combination of silly (as in, out-of-place), and clueless… but also poignant and relatable. I see the stereotypes of Indians used in Western comedy shows as way too over-the-top. These stereotypes walk too close to the border of offense, and often cross it. They create more of an inclination to simply laugh at their outsider-ness rather than to empathise with it. Creating empathy for the fedora man is a strong element in our work. Rakesh paints him in a very tender way, as a very gentle character.

Atkinson’s book was originally published shortly after the Sepoy mutiny – a highly contested time in history. Now, at least here in India, our adversaries are mostly our own kind, brought on by our own actions/inactions. Would you ever consider culturally acclimatising the fedora man – perhaps giving him a tan?

The problem I see is that people who view my work tend to fall into two very separate camps. There are those who wish to analyse them politically, which of course is natural as there is so much emphasis upon the political in today’s contemporary art. Then again there are those who see these works as the continuing adventures and misadventures of the fedora man as a character they have come to know and love over the thirteen years of his existence within our art. I think of art not only within the contemporary, but as a kind of visual messaging through time… So, in ways, the fedora man is a chameleon: at times the gentleman outsider, and at times the man doing his best to be a local. That is the way he has always been, and that is the way I hope to keep him.

Waswo X. Waswo & R. Vijay, ‘The Intruder’, based on George Francklin Atkinson’s ‘Curry and Rice’. All Images Courtesy of the Artists and Monsoon Malabar.

Share