In Touch with Reality: Braille Graffiti

Students in Kolkata’s Jadavpur University create India’s first Braille graffiti and broaden the conversation on inclusion and disability

Godhashri Srinivasan

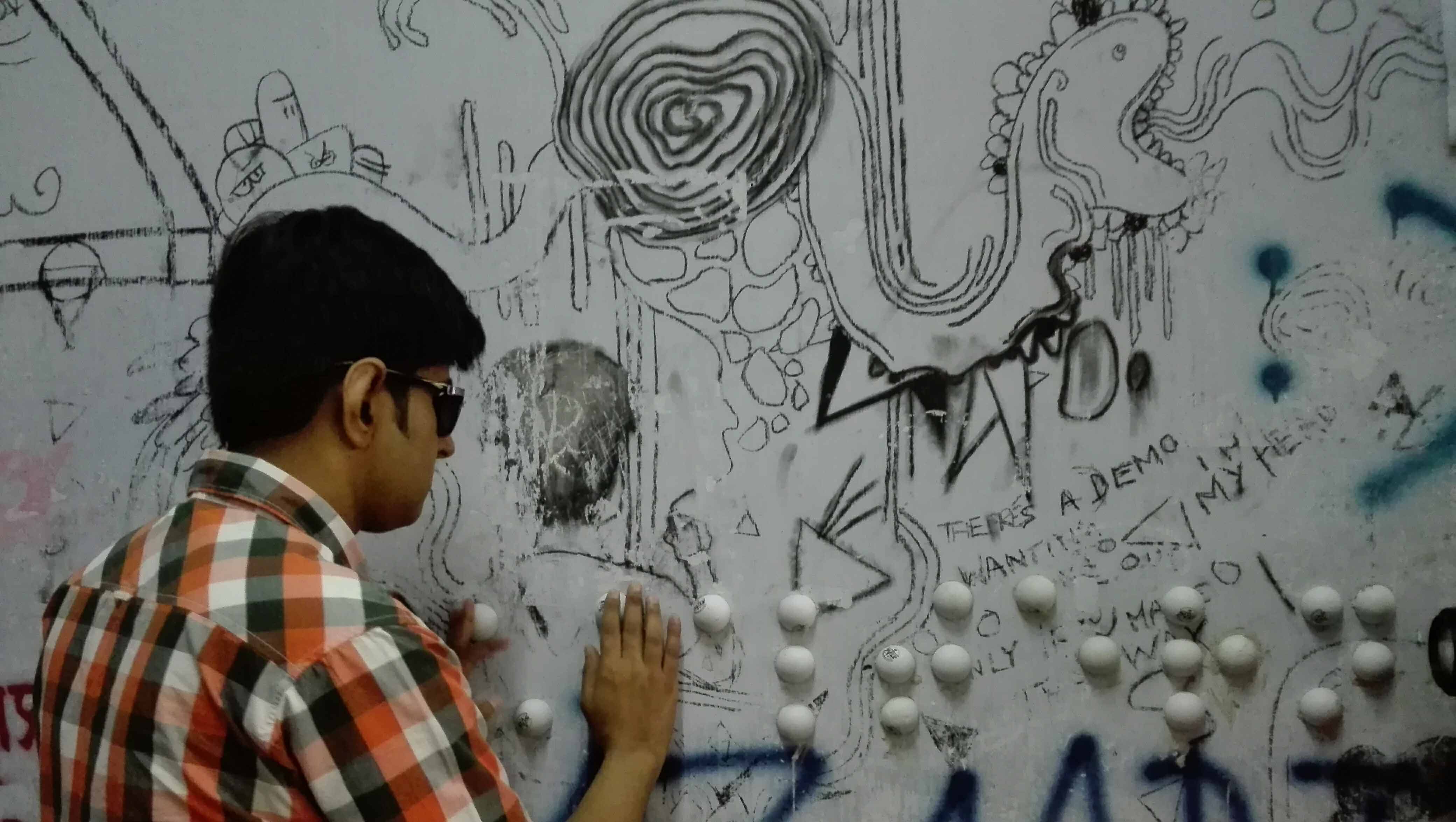

In Jadavpur University, Kolkata, six students installed India’s first Braille graffiti. One reads ‘Subaltern’ at the UG Arts Building, and the other is ‘Look’ at the English department, both made with tennis balls cut in half and stuck on the walls with plaster. The project, a result of an internal assessments assignment, was inspired by the work of a European artist who calls himself ‘The Blind’. ‘Braille graffiti accomplishes inclusion by inverting the notion of disability and subverting the “status quo,”’ said Ishan Chakraborty, the coordinator and assistant professor at the English department.

And it was his students, Subhradeep Chatterjee, Chandrima Mukhopadhyay, Anik Mandal, Manikankana Sengupta, Utsa Ghosh and Emon Bhattacharya, who took it upon themselves to make the campus culturally inclusive and artistically dynamic for the visually disabled. In his paper, ‘Art and Disability: Introjections and Underlying Politics in Subcultures and Genres,’ Chatterjee talks about the work done by The Blind, and how a subject that is essentially serious is given a light-hearted, ironic perspective. For instance, some of the artist’s installations have included ‘Love is blind’, ‘Open your Eyes’ and ‘Do not Touch’.

‘Braille graffiti is meaningful and decipherable only to a particular set of people,’ said Chatterjee. ‘If you’re visually disabled and know Braille, you can read the graffiti, but you need to be informed about it by someone who is visually able. Then, the visually disabled person can decipher it and tell the visually able person, the one who saw it first.’ This turns the ableist notion of disability on its head, and the politics of the seen and unseen become intrinsic to the dialogue.

‘We often think of inclusion in terms of physical accessibility, like ramps. Most ramps are not really wheel-chair friendly. These tokenisms come as an afterthought. We think of reservations, quotas, free education and incentives, because in India disability and poverty is intertwined. We don’t have audio-description theatres. In fact, not many of us know about the Anubhav Gallery at the National Museum in New Delhi, which lets visually disabled visitors touch tactile exhibit replicas,’ explained Chakraborty.

But Braille graffiti goes one step further – not only does it add a necessary layer of nuance to the conversation on inclusion, but it also subverts our carefully constructed notions of normalcy. ‘When you see these tennis balls stuck on the wall in bizarre, peculiar patterns, it immediately creates discomfort. It disrupts the comfort zone of the ableist world. As subalterns, we always want to shake the status quo,’ added Chakraborty.

Share