History for the Keeping

Museums often tell their own stories in voices from the past that quietly settle into our pockets, reminding us of our roots and the ground beneath our feet

Siddhartha Das

Last summer, as a full grown man of 42, I went with my father and my five-year-old nephew to the National Museum of India, armed with drawing books, a clutch of pencils and a foreboding sense that this may not be the cleverest of ideas with a five-year-old. Fifteen minutes in, we were sprawled on the ground by a Buddha sculpture drawing away.

The museum was unsurprisingly empty. It was a weekend and so uninterested students couldn’t be forced to walk through the museum by apathetic teachers. I don’t say this with any disdain. Twenty years ago, as a student of design, I came to do my research project on the Indus Valley Gallery at the same museum. I saw thousands of children forced to go through the museum. The students, teachers and museum staff – all were equally uninterested and uncaring. Students tried to see if they could shake an ancient 4,000-year-old Harappan pot perched on a chipped pedestal, while teachers shouted to keep the children in a line and the gallery attendants had their lunch on the gallery floor.

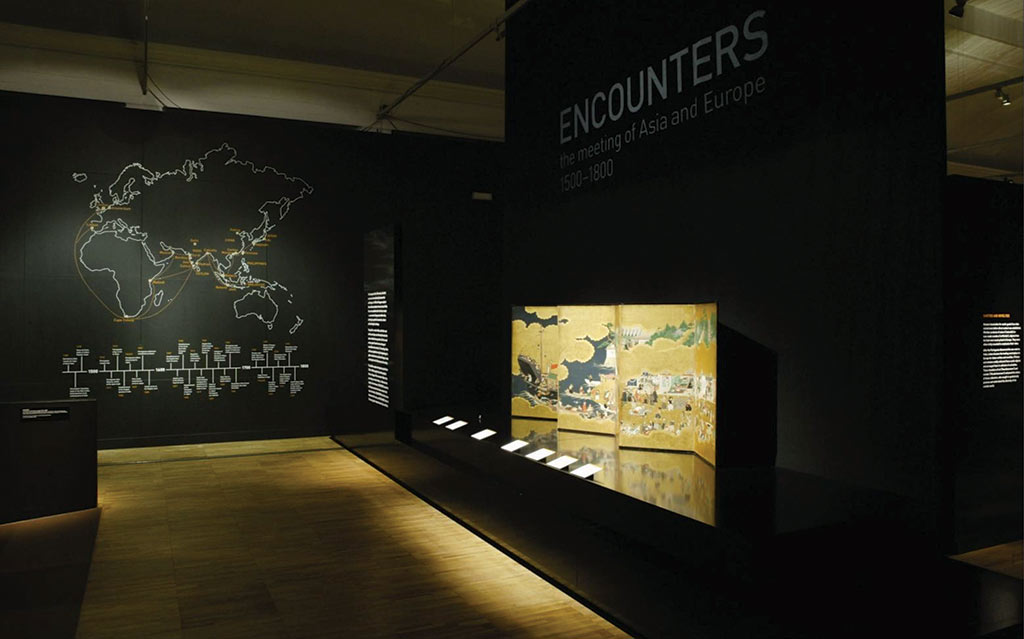

About eight years later, I found myself working at a museum the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, or the V&A as it’s simply termed. During my stint there, I realised how one of the most visited museums in the world rightly recognises that culture can be at the heart of public places, and how it can impact one’s quality of life. The V&A, like other museums, does have the galleries that typified museums of the early 20th century. In these museums, antiquities and pieces of natural history by the thousands were displayed in scale and proportions that seemed wondrous. The Palaeontology Museum, one of the many parts of the National Museum of Natural History of France, is a prime example of this. It was fascinating to take my nephew to it. Well, at least for the first 10 minutes.

It is always interesting to see what the word ‘museum’ evokes in most people. They are often seen as colonial vestiges, housing fossilised objects in rarefied milieus run by liberal academics. No one wants to go to such a space of their volition. As someone who works actively to ensure that this doesn’t happen, I began to search for what museums could be, especially in today’s context.

The International Council of Museums describes the museum as an ‘institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment’. This is far from the Indian reality. I am currently working on four museum projects and I know that there are others like me with a similar vision for a museum.

In my view, in countries like ours where there is a continuity of culture, museums can be that exciting platform that makes the passage of time and the inherent continuity of it more apparent. A Harappan pot is made in almost the same way after about 4,000 years in the village of Lodai, Kutch. A bronze sculpture, like those of the Cholas, is made similarly by a lost-wax process in the villages near Tanjore. These institutions could be the place that anchors our sense of rootedness, our identity. Our sense of identity does not, I hope, come more from fighting our own people separated by bizarre machinations of politics.

It is here that the role of museums makes these continuities apparent, be it through their built heritage, their collection of historical antiquities or their ethnographic approach. The Mehrangarh Fort or the City Palace Museums of Jaipur and Udaipur in Rajasthan are obvious examples of what most occidental romantics associate with India. A similar resplendent case could be made for the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul, a country as troubled as ours with neo-patriotism. Yet, they provide a fascinating narrative of a layered past.

It is, however, the ethnographic museums that are my favourite. They engage and challenge the visitors to understand and dispel the stereotypes one has of other societies. The Ethnology Museum at Leiden, Netherlands, is possibly one of the edgiest in the world, if seen from this perspective. This sleepy university town in the Netherlands has re-envisioned how societies are represented and understood. To have a Jamaican as their chief curator allows this to be reinterpreted more interestingly. When I met Wayne Modest, the Chief Curator, earlier this year, he mentioned how he was perceived by an increasingly right wing society, and how his intellect and his skin colour defied the common perceptions. He wanted to ensure that the museum would challenge these notions.

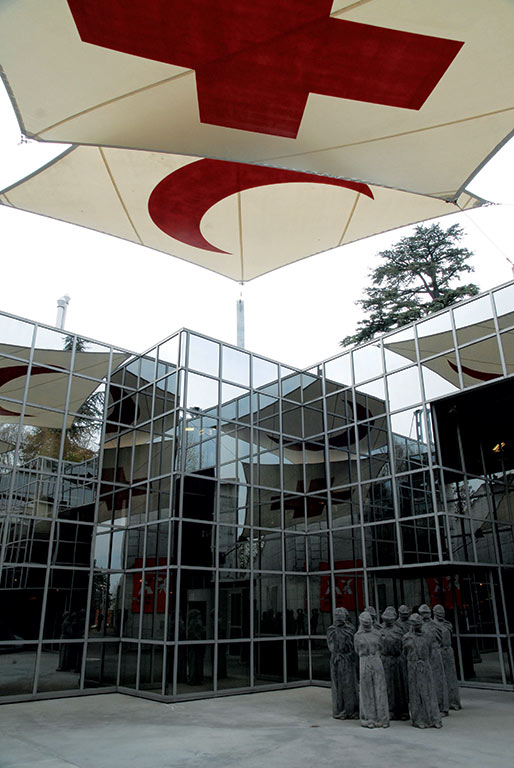

Possibly, one of the more interesting cases of how museums can influence society is the Red Cross Museum in Geneva. It sees itself ‘as a place of awareness and reflection, a museum of history and society helps us understand the world. What distinctive contribution can it make in the era of the Internet and instantaneous information? Exhibitions have the unique privilege of being able to draw on all disciplines of knowledge and, in parallel, to make simultaneous use of all media to put them across’.

The museum is dedicated to the notion of the Humanitarian Adventure, defending human dignity, restoring family links and reducing natural risks. It showcases three contemporary problems that are of concern to us and will affect our future for decades to come. As one of the nine creative professionals invited to redesign it, it made me realise how museums truly can influence people.

As I write this, it becomes all the more apparent that this is not the dream of a country our grandparents fought for. And, therefore, the role of museums is even more poignant that can hold up a mirror to us and help us ‘be the change you want to see in the world’.

All Images Courtesy of Siddhartha Das

Share