Road to Restoration

Tracing the patterns of history in something as tangible as architecture can be daunting and exhilarating, as is evident in this comprehensive study of ‘The Governor’s Residence in Tranquebar: The House and the Daily Life of Its People, 1770–1845’ edited by Esther Fihl

Esther Fihl

The restoration of a house means moving backwards in history; not to one special date or year, but something that is a lot like storytelling. For me, restoration is a form of storytelling; the task of assembling a building’s story. This discourse on restoration served as our point of reference from the outset. The combination of archival information and the information visible in the layers of constructions and changes revealed many histories about the building which, as in storytelling, are made up of a major story interlaced with minor ones. In fact, the guidelines issued by the project’s steering committee for INTACH can be summarised as follows: to restore what remained without removing parts of the overall story in the building. The key focus of this assignment was to maintain the full life story of the building. Not just the period when it served as the governor’s residence, but also – to the extent that this was possible – a time before that as well as afterwards, in the period following the British takeover and after Indian independence.

When we looked at the cultural encounters taking place in and around the house from the 1770–1845, they seemed to reflect processes of making something opposite. Both Indians and Europeans used each other as a kind of mirror reflecting cultural otherness in relation to their own cultural self-identifications. They encountered reversed social rules and agendas; and in a cultural sense they grappled with each other and created new shared social terrains that were neither Indian nor European, but something creative and new in itself (though they were not free from power relations). And this extended to the arts, as well. In this exhange between Indians and Europeans, the experimenters and subjects reversed rules that led to cultural inventiveness and hybrid styles. This accounts for the hundreds of naturalistic ‘company paintings’ brought back by Danish civil servants serving for years in Tranquebar. The presence of both European and Indian artists trained in European techniques, which made the growth of new forms of portraiture possible, especially in the late 18th century developed at the royal court of Thanjavur. Several of these miniature paintings ended up in Danish museums along with large collections of other material items brought from Tranquebar. In the museums, these objects, till today, serve as tools to reflect and disseminate the history of the life and ideas of people in and around Tranquebar.

An excerpt from the book

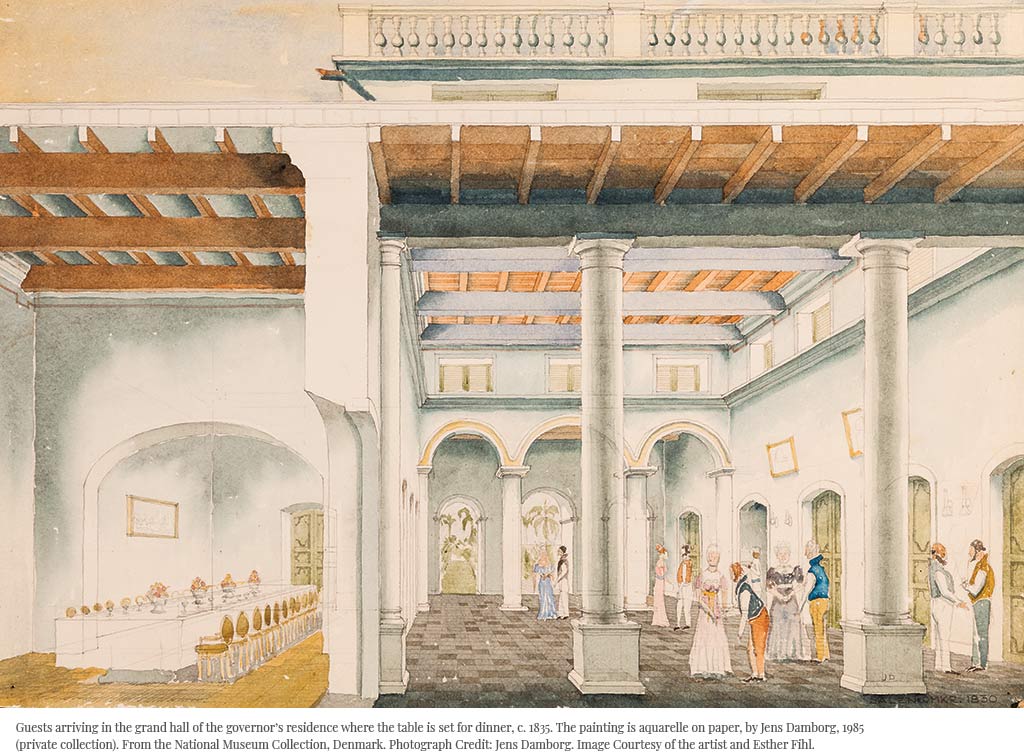

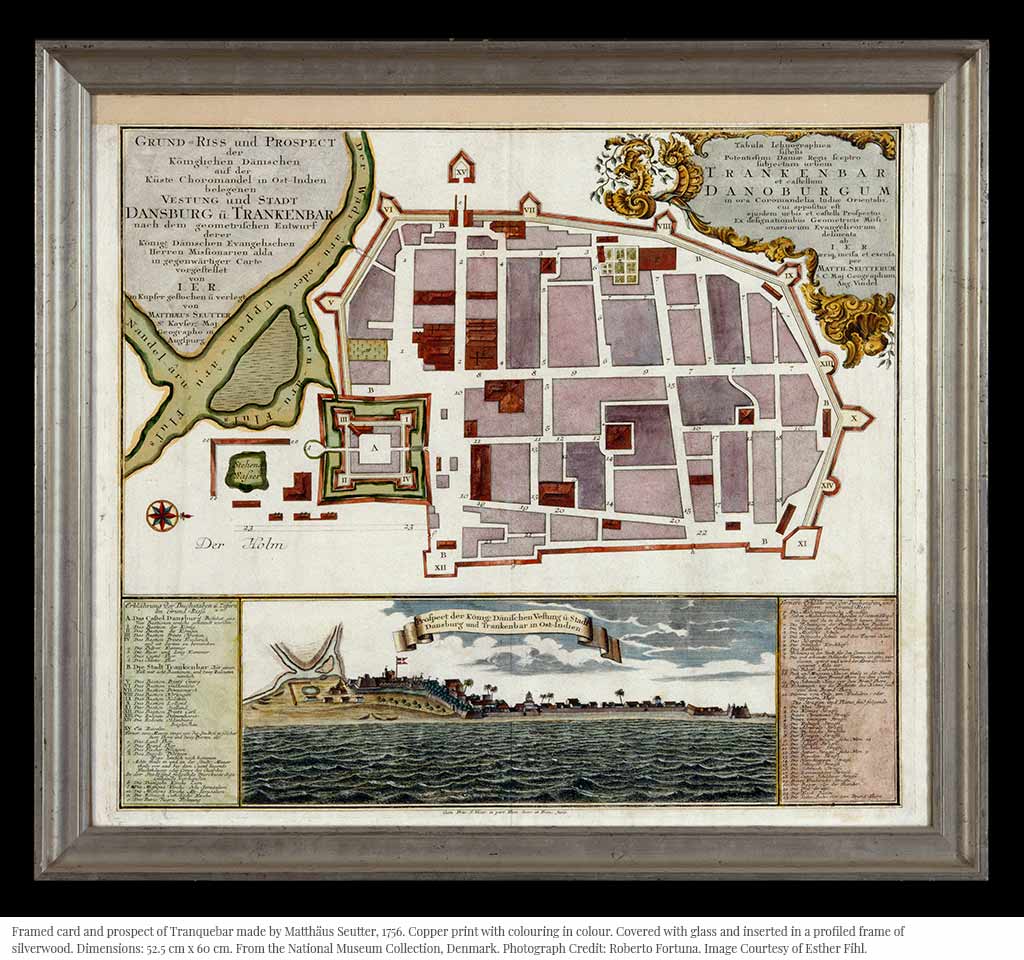

From the establishment of the Danish trading station in Tranquebar in 1620 the military fortress of Fort Dansborg was used as the administrative office and also served as the governor’s official residence. In the late eighteenth century, however, the rooms at the fort were considered too narrow and old-fashioned, and so in 1784 the Danish crown bought an existing house in the town, immediately opposite the fort and its parade ground. This house was furnished as a prestigious home and office for future Danish governors in India. One of these was Peter Anker, a progressive governor who served in Tranquebar from 1788 till 1806. He was a skilled painter with a profound interest in both Indian and European art, and he put his indelible mark on the architectural embellishments of the house. He transformed it into the most spectacular house in town and it continued to function as the residence of the Danish governor up until 1845 when, because of the financial problems arising from the strong competition from British trade and politics, the trading station was handed over to the British for a minor sum of money.

To paraphrase the cultural geographer David Lowenthal’s seminal book, ‘The Past is a Foreign Country’, the following chapters deal, methodologically speaking, with the past as a ‘foreign country’ and from multiple perspectives. We explore clashes between Indian and European terrains that are politically, socially and culturally distant and different to us, not only in time but also in form and content. In doing so we seek to deal with these two terrains analytically, as if they were both inhabited entirely by cultural others whose mentality and cultural habits we cannot take for granted but instead have to comprehend. We must describe the interactions of these various cultural others as they form new common terrains and mirror themselves in each other, like a looking glass held up to reflect their own cultural or national characteristics. In that sense our analysis of the house, its décor and the life of its people and their Indian setting is grounded in detailed studies of architectural and ethnohistorical terrains where we seek to be respectful of the real, which is both near and far, complex and simple, familiar and strange, local and global. As described by Jean and John Camaroff in ‘Ethnography and the Historical Imagination’ our accounts of the multilayered and multicultural life in a small and marginalised trading station on the south Coromandel Coast of India in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries will likewise necessarily be imaginative in their understanding of the material and interior world of others.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Governor’s Residence in Tranquebar: The House and the Daily Life of Its People, 1770–1845’ edited by Esther Fihl. Published by University of Chicago Press, December 2017. ISBN: 978-8763543880.

Share