All is Well

India’s stepwells, a rare mix of functionality and aesthetic, has in its mix an old reverence for visual extravagance steeped, quite innocuously, into everyday life

Suzanne McNeill

A black-and-white photograph taken in 1971 by Raghu Rai, one of India’s most famous photographers, captures the moment when a young boy dives from the crumbling masonry of the Agrasen-ki-Baoli in Delhi into the dark waters of the stepwell. Beyond rise the modern tower blocks of the city. It is an image of contrasts, ancient and modern, shadow and light, and one that disorientates the viewer in another way. To take it, the photographer must have descended the steps into the man-made chasm to stand at the water’s edge, lifting his camera up to ground level. As Rai would have discovered, stepwells are barely visible above ground and their function and aesthetic can only be appreciated on entering them.

*

There is a long inscription on the 16th-century Dada Harir Stepwell, part of which reads:

“… In the Gurjara country, in the glorious city of Ahmedabad […] Bai Sri Harir caused a well to be built in order to please God, in Harirpur, situated to the north-east of the glorious city, for the use of the eighty-four lakhs of the various living beings, men, beasts, birds, trees, etc. who may have come from the four quarters, and are tormented with thirst … As long as the moon and the sun [endure], may [the water of] this sweet well be drunk by men! … [The lady] Bai Sri Harir by name built this well at great expense, in order to benefit the world.”

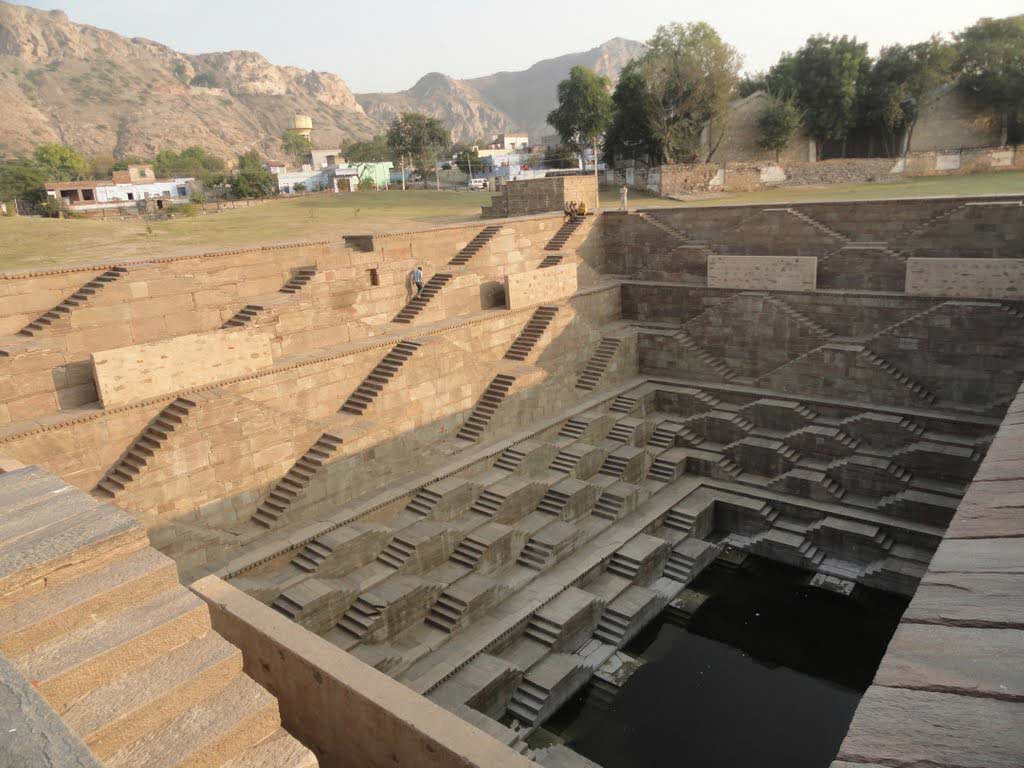

This extract reflects the different motivations – religious, practical and public-minded – that inspired benefactors, a significant number of whom were women, to commission stepwells. Described as India’s forgotten architecture, thousands of these magnificent water buildings were built across India from medieval times onwards but they are particularly associated with the arid, north-western states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, where there is a profound shortage of fresh water and the seasonal monsoon rains quickly disappear into the ground. Sunk into the earth to the level of the water table, stepwells transformed into huge cisterns during the rainy season, and were designed to give access to the receding water levels during the rest of the year.

Rudimentary stepwells have been constructed since the 3rd millennium BCE and evolved from basic pits in sandy soil to elaborate and complicated multi-storey structures dug deep into the ground. The earliest existing stepwell may be the Jhilani Stepwell, which appeared in Gujarat’s Saurashtra region around 550 CE. It was built of stone blocks that were laid without mortar, an innovation in stone construction that made stepwells possible. Over time, three major elements came to define the stepwell: water fed into it through cylindrical well shafts sunk through the rock, from which water could be drawn in buckets; a stepped corridor or staircase that led down several storeys into the vast excavated and stone-lined trench, ending at the water level of the well; and subterranean passageways and ornately carved open chambers and galleries that offered cool retreats.

From the 11th to 16th century CE, the construction of stepwells – called Vav in Gujarati and Baoli in Hindi – hit their peak, evolving not only into astonishingly complex feats of engineering but also as stunning works of art, built under the patronage of aristocratic families who sought to earn merit through good deeds. They were built with beautiful stone, the colour of which was reflected in the open pools and wet surfaces as the water level rose and fell in line with the seasons. As with the temple and palace construction of the medieval period, stepwell architecture provided a framework for ornamentation. Hindu artists carved sculptures and friezes that depicted gods and goddesses, celestial dancers and musicians, and heroes from Hindu epics alongside scenes from daily life such as milkmaids churning butter, women combing their hair and royal figures attended by their bearers. There were scenes of battle, fighting horses and elephants, and the columns, brackets and beams were alive with floral, geometrical and animal motifs. Commissioned by Queen Udayamati, the Rani-ki-Vav in Patan, Gujurat, was built on the now-disappeared Saraswati River between 1022 and 1063 CE. It was designed as an inverted temple, and descends 23 metres through a stepped and tapering corridor to the tank. It is divided into seven terraced levels, each decorated with multiple, pillared pavilions adorned with sculptures of the deities and their consorts. Smaller bands of sculpture show dancing and musical scenes, and girls applying cosmetics. Islam’s more austere traditions contributed filigree-like scrolls of motifs of flowers and leaf-vines to this decoration. The two styles were to synthesise and interact in many of the stepwells built under successive Hindu and Muslim rulers.

As utility and as a work of art, stepwells became places where people gathered and socialised – they came to drink and bathe in the water of the well, to wash clothes and water their livestock. Women were usually associated with these wells, for it was they who collected the water, and the stepwells would have provided a communal outlet in what may have been restricted lives. Perhaps, they gloried in the aesthetic beauty of the stepwells, simple villagers bathing in magnificent surroundings. Stepwells were also for prayers, meditation and offerings to the deities whose images formed the backdrop to these activities. Whilst the ‘newer’ gods of Hinduism were enshrined in temples, the deities residing in the early stepwells were related to the divine and semi-divine beings – ancestral gods, nagas and yakshas worshipped at river edges and beneath old trees. Stepwells were also associated with fertility. Women prayed to the goddess of the well for her blessings and offered votive gifts.

Some stepwells continue to be used as shrines today. Part well, part temple, the Rani-ki-Ji is the most famous of the more than 50 tanks and wells in and around the city of Bundi in Rajasthan. It was built in 1699 by Rani Nathavati, the second wife of the king. Cast aside after she bore him an heir, she devoted herself to serving her subjects and built 20 wells including the 46-metre-deep Rani-ki-Ji. Two hundred steps descend to the water below, passing under a high, slender gate, archways decorated with S-shaped brackets and exquisite elephant carvings. There are places of worship on each floor. The dual benefits of shrine and water enriched with minerals ensured that stepwells were places of folk healing. They also offered a retreat in the hot season, as evidenced by the numerous platforms, galleries and ledges, the stone benches with backrests, staircases and circumambulatory passages around the wells. People took advantage of stepwells as cool havens for the air was usually several degrees cooler as they descended towards the cistern.

*

A new audience is discovering India’s stepwells: movie-goers. Just as Rai captured the sense of a place lost in time, filmmakers have made the most of these abandoned monuments as atmospheric, sometimes brooding, settings. The Agrasen-ki-Baoli recently featured as a location in Aamir Khan’s sci-fi film PK, and Chand Baori was transformed into the grim prison in the Hollywood film The Dark Knight Rises. Shah Rukh Khan’s fantasy film Paheli used the Hadi-Rani-ki Baori in Todraisingh, Rajasthan, as the stopping point for the separate but related journeys of its hero and heroine: they both meet the same mysterious stranger at the well. Seemingly hidden in plain view, these neglected works of art are reclaiming their role in the communal space.

Share