A Tale of Two Kalis

For most of us, Kali appears to be a negative force, but the origin stories of cosmic battle point to the dual nature of her aspect, which is embodied in the seemingly opposite meanings of her iconography

Suzanne McNeill

The Kolkata taxi driver who offered to take us to the Kali Temple to see a goat being sacrificed was simply being helpful. Our attempts to locate a small, commercial art gallery were being thwarted by the chaotic traffic. We were hot and tetchy, and the city’s baffling one-way system had just switched direction, so we had started to circle again. If we went straight there, he told us, we’d get a good view of the ritual. Not a moment too soon, we spotted our gallery.

*

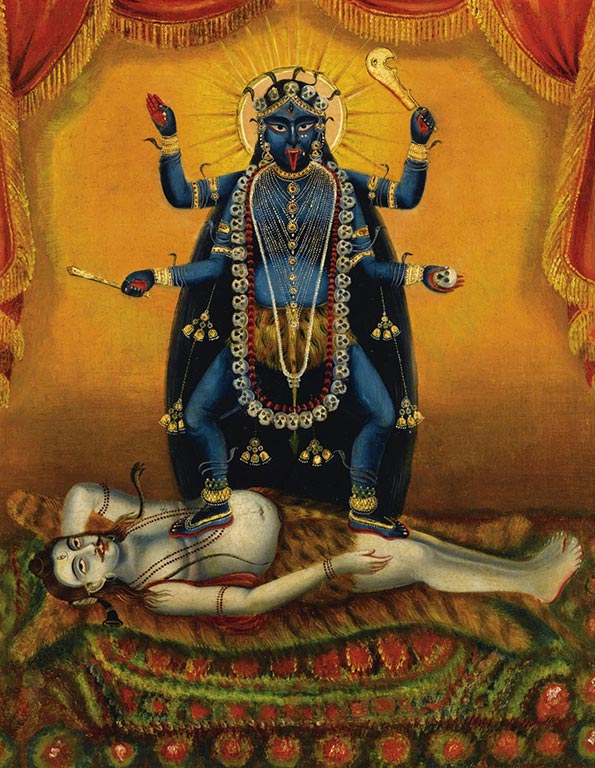

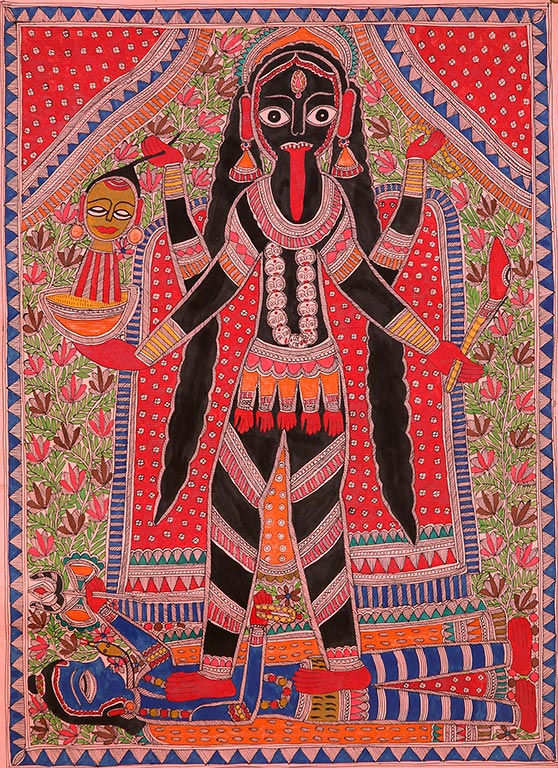

Generations of artists have found awesome beauty in the figure of Kali and the images and symbols associated with her. She became a popular subject for artists in 19th century Bengal, where, long before Raja Ravi Varma, the early Bengal school of artists had started to experiment with oil as a medium, painting familiar subjects from mythology in a distinct indigenous style. They took the references for their iconography from the sculptural traditions of the goddess that already existed in terracotta and stone, and reinterpreted them with an emphasis on anatomical representation that appeared real.

These were dramatic visualisations that represented the goddess in a full blood-thirsty and ghoulish style. To the Europeans who commissioned these paintings, Kali must have appeared as an icon of destructive and uninhibited madness, displaying a terrifying insanity. Where traditional images of deities such as Parvati and Saraswati acquired a soft and gentle demeanour that conveyed their benevolent aspects, Kali was depicted rampaging across the canvas, wild and frenzied, and these paintings helped establish the iconography of the goddess that is familiar today. Her name is the feminine form of the Sanskrit word kal meaning ‘black’, the darkness of the void, and her place of abode is said to be the cremation grounds. So her body is always black or indigo and garlanded with a necklace of skulls. Her tongue lolls bloodily from her mouth and her four arms hold aloft her attributes including a sword and a severed head, sometimes still dripping blood. She dances in anger, in abandon, and Shiva (Shiva!) lies prostrate beneath her feet. Associated with violence, Kali is the goddess of death and of doomsday.

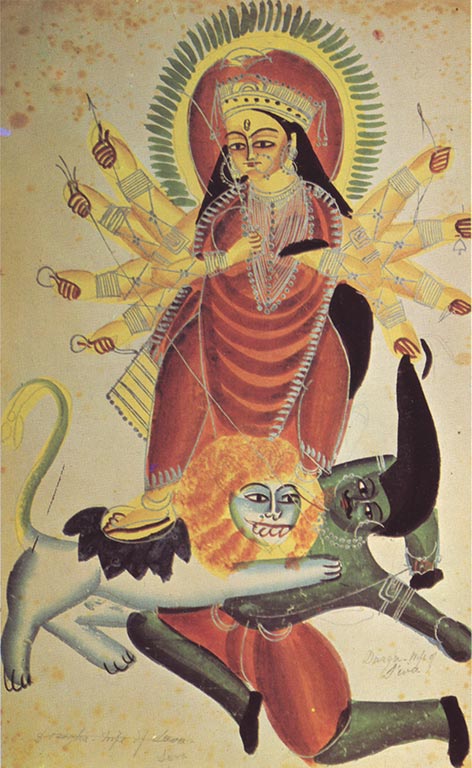

Kali may have originated from a folk deity worshipped by rural Bengalis, but her first recorded appearance is in a piece of Sanskrit literature in the 6th century CE. The Devi Mahatmya, a treatise within the Markandeya Purana, tells how Kali sprang from the forehead of the warrior goddess Durga during battle as a manifestation of Durga’s anger. In fierce and emaciated form, Kali beheaded the asuras, the demons, on the battlefield, stringing their heads on the garland she wears around her neck. Another story is that she was born from the dark skin shed by goddess Parvati (who thus became ‘the Fair One’), and she is transformed from Parvati to Kali in a third story of origin: as Parvati, she absorbs the poison swallowed by Shiva that arose from the churning of the ocean at the point of creation, leaping from his throat as Kali to despatch the demon Daruka. In yet another version of her story, she is the fusion of the divine energy or shakti of the gods, manifested to confront the terrible demon Raktabija. Wherever a drop of Rajtabija’s blood fell to earth, another asura of his stature arose; Kali devoured all the asuras who existed, then cut off Raktabija’s head and drank his blood, ensuring none fell to the ground to produce more demons.

Commentaries on these texts describe Kali as appalling and cruel, and her zeal for violence overtakes the righteousness of her acts, for her vehemence is aimed at the forces of evil, ignorance and sin, and their destruction makes way for the change that leads to enlightenment. Her victory brings universal relief and she is adored and worshipped as the main deity of Bengal whose fearsome form both gives and takes life. To non-Hindus, she appears to be a negative force, but the origin stories of cosmic battle point to the dual nature of her aspect, which is embodied in the seemingly opposite meanings of her iconography.

Kal has a second meaning, ‘time’, and the blackness of Kali’s figure symbolises not only eternal darkness but the promise of new creation. Her naked appearance represents freedom from constraint, and the head and the sword she wields symbolise the severance of the ego, enabling the soul to escape the physical world and achieve moksha. One hand is held in a gesture of blessing. Her tongue sticks out in embarrassment, not blood-lust, for she failed to recognise the body of Shiva beneath her feet – he is lying in her path to stop her destructive rampage – and she has realised her mistake.

In spite of her seemingly terrible form, and also because of it, she is regarded by her devotees as a great protector – Kali Ma – the Mother of the whole Universe. She is the embodiment of feminine energy, creativity and fertility, for without her pulsating energy, existence itself would lie inert.

Several of India’s modern artists have portrayed Kali, including K.G. Subramanyan and M.F. Husain, and most retain the goddess’s distinctive iconography, whilst reinterpreting her form according to their trademark styles. The most individualised versions of Kali, however, belong to the artist Tyeb Mehta.

It was as a primordial, fantastic image that Mehta first approached the figure of Kali during the 1980s. Before then, he had not drawn explicitly on religious tradition or material and much of his work was secular in content, preoccupied with themes of humans in states of raw suffering. Biographies of the artist refer to his early experience of aggression and upheaval. He worked as a cinematographer at the end of World War II and witnessed a murder during the Partition. Manifestations of violence, struggle and survival were to become a primary concern of his art.

Mehta was drawn to Kali during his residence at Shantiniketan. The school valued the integration of modernist art in a larger history of Indian art and folk culture, and Mehta turned to indigenous themes and subjects. He was stimulated by the vitality of rural and tribal culture that was celebrated at Shantiniketan, and his monumental Shantiniketan Triptych was formative to developing his own version of the goddess’s iconography. An ambiguous figure, who is based on his observations of a devout, elderly woman known to the school community, dominates the centre of the canvas. Her multi-armed body is split into red, white and black, and she has two faces, one carrying an expression of serenity, the other fierce and malevolent. The triptych preceded Mehta’s series of paintings of Kali, six full-length and bust portraits of a fearsome and grotesque female figure that capture the goddess’s violent power.

The traditional attributes of the Bengal paintings are absent from Mehta’s Kali images. There is no sword or garland of skulls, no Shiva beneath her foot, no staging or sense of narrative. Yet, her conventional iconography is there in part, in her swollen blue body, her monstrous, distorted face, which is framed by hanks of unkempt hair, and her red mouth, gaping and fleshy. The goddess appears to be arrested in a moment in time, caught in a dreadful struggle.

The last painting from the series loses even those few attributes. It is executed in olive greens and browns. The line is minimal and the figure emerges from the black background, delineated by the fields of colour. The grim, red mouth is gone, and so are the distorted features. Her breasts and stomach are full and rounded, maternal even, and her hand reaches out towards the viewer. There is little sense, however, of redemption in the painting – the outstretched hand does not offer a blessing.

Mehta’s images of Kali are both ancient and contemporary. They hark back to the narrative precedents of the Bengal works, and take advantage of the complex transcendence of the goddess. They also represent a move from Mehta’s earlier work, which explored ideas of inner torment, to suggest the shared suffering of wider society, of the public domain. Perhaps it is no accident that these paintings are the output of Mehta’s final years, as his Kali is the embodiment of the presence of death in life.

Share