Faces in the Water

As physical ‘masks’ become part of our life, we take a look at artists working with different aspects of ‘faces’ and the things that lurk beneath the surface.

Praveena Shivram

Long before the world went into isolation, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama voluntarily moved into a psychiatric asylum in 1977. She did this to (a) cut herself off from society, and (b) due to her mental health issues. She has lived and worked from a studio close to the asylum, since. She is 91 years old.

Often called the ‘princess of polka dots’, Kusama’s art, much like her, is a psychedelic embodiment of things we consider sacred and significant swirling with things that we consider abnormal, or as we seem to call it these days, the ‘new normal’. In her interview in 2015 for Louisana Channel, she said, ‘When I create my work, I am not forcing to bring the polka dots into it – subconsciously, it became polka dots always by itself. I am not sure if it is a suggestion from my illness, or if I wanted to do that because I’m totally absorbed in creating the piece… when I’m creating my work, so everything disappears around me, and my hands create my work. And then, I don’t know… as an artist by myself… I have been thinking that my big job is to glimpse my vision.’ When she speaks, she has a folded handkerchief, also with polka dots in it, which she is constantly moving around in her hands. She has straight hair, cut short and falling till her jawline, dyed a bright orange. And her clothes, too, are covered with polka dots. ‘After all, well… the moon is a polka dot, the sun is a polka dot, and then, the earth we live on is also a polka dot. And also you can find them in a form of the eternally mysterious cosmos, too. And, through them, I wanted to see a philosophy of life.’

For three years, we have attempted to interview Yayoi Kusama for Arts Illustrated. At one point, every single theme seemed to fit into her philosophy, because, really, everything is a polka dot, including the corona virus currently holding the world in its grip. For Yayoi, dissolving herself – her various hardships and struggles of childhood, of her time in New York, of claiming space as an artist, her deteriorating mental health – into the repetitive polka dots, in allowing them to consume and swallow her whole, there is the opportunity to rearrange the many dots that make her up, the many dots that make up the world around her, in a way that becomes comforting, while for us, it is an opportunity to step into a fragmented, fractured reality, that is disconcerting in its fullness but familiar in its parts. Yayoi’s conviction is born from that space of the uncertain, the landscape that shifts without necessarily coming to a place of rest, while we step into Yayoi’s famous ‘Infinity Rooms’ that use mirrors to reflect her installations into infinity, from an interminable sense of certainty, that we momentarily leave outside, like footwear, knowing it will still be there when we step out the door. Now, as we frantically search for our missing shoes and find our bare feet rooted in rigid isolation, Yayoi’s polka dots seem like the epiphany that was waiting to happen.

During the course of the interview – not mine, we were always politely declined – Yayoi breaks into songs, twice – songs she has written herself. One of them is this:

Swallow antidepressants and it will be gone

Tear down the gate of hallucinations

Amidst the agony of flowers, the present never ends

At the stairs to heaven, my heart expires in their tenderness

Calling from the sky, doubtless, transparent in its shades of blue

Embraced with the shadow of illusion

Cumulonimbi arise

Sounds of tears, shed upon eating the color of cotton rose

I become a stone

Not in time eternal

But in the present that transpires

– Song of a Manhattan Suicide Addict, 1974

***

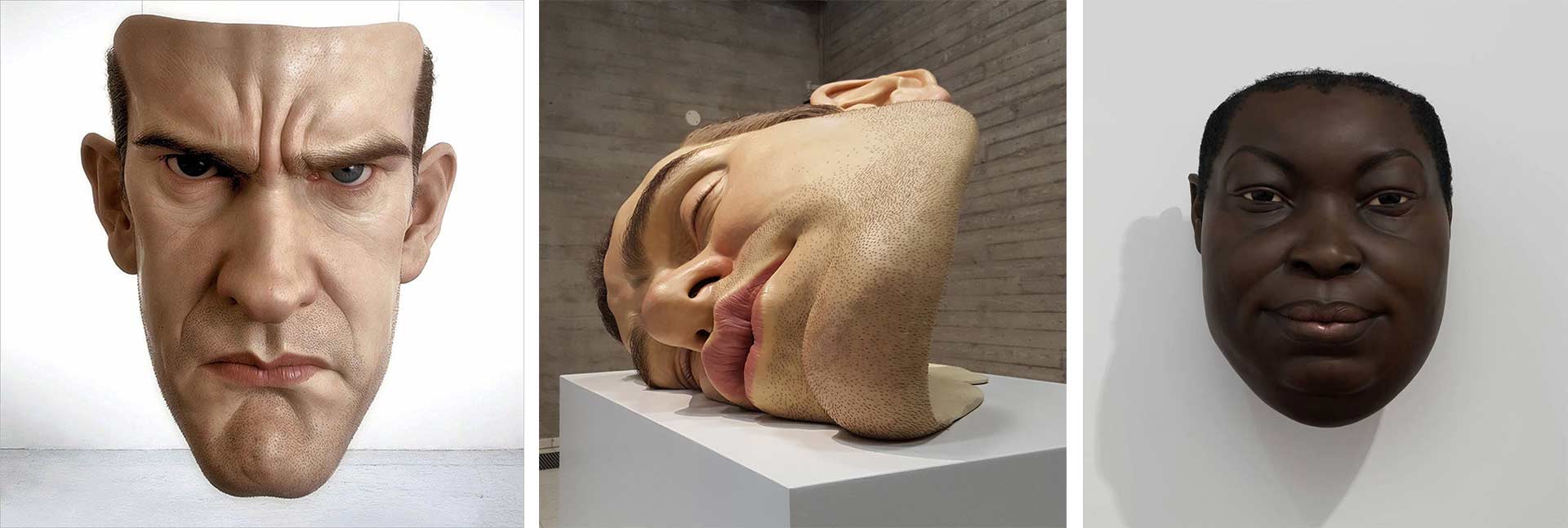

Two men carry the face from within the crate to an open pedestal. The face, four times the size of a regular face, appears to be asleep, lying down sideways, the skin pushed in, the forehead mildly scrunched up, the mouth slightly open, the eyes looking like they are dreaming, with a faint stubble around the chin and cheeks, and hair that looks to be thinning. Titled ‘Mask II’, this is part of American sculptor Ron Mueck’s hyper-realistic sculptures. He creates massive human figures using silicon, fibreglass or acrylic, cast from clay models, and it is in the detailing – and by that I mean even the pores on the skin, the discolouration and pigmentation that come with age, the expression, the wrinkles, the veins – that Mueck shines. But it is in this particular set of sculptures – Mask I, II and III – that I am drawn too. Mask I and II are self-portraits, where Mask I is a full frontal angle, the face looking directly at you, eyes open and pulled together, the expression of someone who is not pleased, belligerent even, while Mask III moves away from the self-portrait, into a dark-skinned face that looks like a cross between the laughing Buddha and Whoopi Goldberg. If the face that we see is awash in detail, then the face that we don’t see, the one behind, is empty and hollow. It’s a mask.

Ron Mueck, who spends hours in his studio, over months and years, to make the sculptures come alive, works in silence. He also doesn’t give interviews. Even in the documentary made by photographer Gautier Deblonde, Mueck doesn’t speak (the clause was no interviews), letting the silence of the camera interact with the silence of his movements. ‘Ron Mueck doesn’t speak when he is working. He listens to other people talking on the radio, and to the background of noises that filter in from the north London street outside: sirens, footsteps on the pavement, buses,’2 wrote Clare Dwyer Hogg for The Independent UK in 2013 when the documentary was screened. Ten years before that, another writer and curator, Sarah Tungay, in the United States, had slightly better luck. It was a few years into his practice, the early years. ‘I never made life-size figures because it never seemed to be interesting. We meet life-size people every day… It makes you take notice in a way that you wouldn’t do with something that’s just normal,’ he said. While all of his sculptures are full-figured, complete human figures, even if they are sitting in a boat or are under the sheets, it is the mask that occupies an incomplete, albeit nuanced, perspective. ‘The only way I could do a fragment was to make it a mask, because a mask is a whole thing in itself. I couldn’t do a decapitated head or half a body. I have to believe in the object as a whole thing. A bronze bust is an entity because, for starters, it’s bronze and it’s not pretending to be anything other than a fragment or a sculpture. But my things are pretending to be something else as well. A mask is complete already. This is just a different kind of mask. It’s a realistic mask,’ he adds.

A different kind of mask, a realistic mask, one that we now fill with our own faces.

***

Then there is quantum physicist-turned-sculptor, Julian Voss-Andreae, who models his figurative sculptures entirely on the computer using 165 cameras to scan the subject, and then makes his sculptures disappear. ‘My background in physics and my research I participated in allowed me to catch a glimpse of just how bizarre, how weird the nature of reality is,’ he says in an interview for the Insider. And this reality, in all its unpredictable deliciousness, is what Andreae counts on for his sculptures, painstakingly created melding different kinds of metals – titanium, bronze and steel – and built in such a way that as you move from one side of the sculpture to the other, it disappears and appears again. ‘Technology is often my inspiration and a key tool to achieve my visions. But at the end of the day, it is the craft that will make things become reality and successful. Even if a sculpture is made, for example, using 3-D printing, there are always hundreds of hours of intense human labour in there, labour that requires finely honed skills and complete focus on each step of the process. It is that work, both in the design process as well as in the fabrication portion that at the end will show and make the work what it is,’ he said in a recent interview to Art Summit.

Using the form and function of proteins in our body, Andreae offers us a new relationship to human anatomy through the music of metal, his studio resembling an automobile workshop wrapped into a construction site wrapped into a scientist’s laboratory wrapped into our minds. ‘I don’t shy away from complicated problems. I learn to subdivide them into sub-problems and solve those problems one by one, until I get to where I want to be,’ he explains to Insider, and it feels like Matryoshka dolls coming out one after the other – first from Yayoi’s studio, then from Mueck’s, then from Andreae’s – each one breaking apart so they can come together, and then coming together again to be broken apart, and within this vortex of repetition is the answer to experience. That within this vortex of repetition – this vortex, this lockdown – is the answer to the experience that is to come.

***

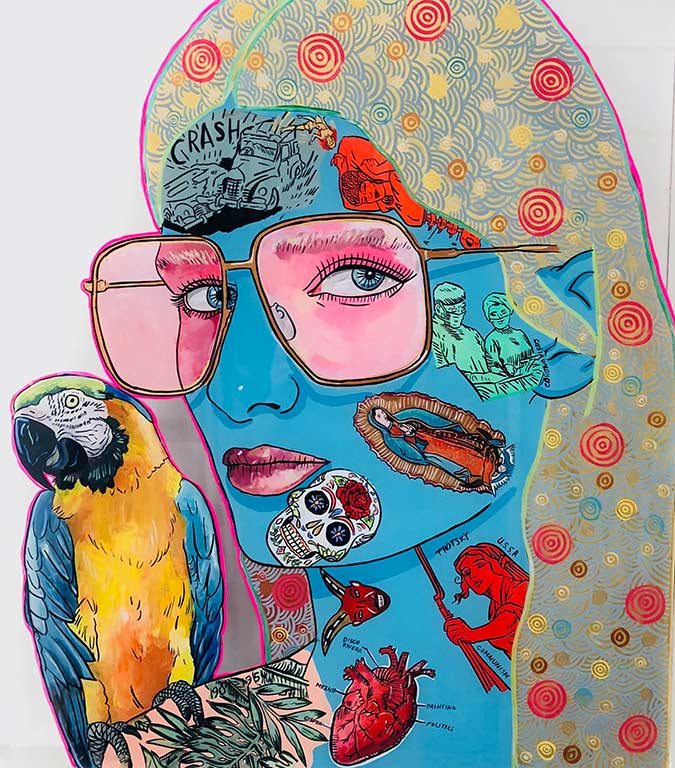

The face I finally settle into is not my own, but that of New Zealand-based artist Sam Mitchell. Not her own either, but the faces that she creates, faces bursting with unexpected imagery – tape recorder cassettes, birds, cats, cartoons, camera, grater, skulls, jellyfish, clapboard, tickets – faces revealing all the stories hidden behind the veneer of skin and flesh, faces looking the same and yet inherently different, faces that speak, faces that don’t, faces that emerge and quickly disappear, faces that are irreverent and faces that are poignant, faces that look into you and faces that look beyond, faces that deliberately distort and faces that look superficially calm – the sea of faces encompass you, blinding you with colour, making you squint harder, move back, move closer, relentlessly holding your gaze, till you know when you look away, you take the face with you, you take it into your own, along with all the faces of the past and all the faces of the future, irrevocably entwined in Mitchell’s arresting artworks, and irrevocably entwined in a pandemic reality. Every face we see, is ultimately our own. ‘It’s multi-layered narratives in the end. Some you will get, some you won’t get, but that’s the whole fun of it,’6 said Mitchell in 2013, at the opening of her exhibition, Hips, at Bartley & Company Art, Wellington.

And, maybe, that is the point. A polka-dotted, masked, constantly appearing and disappearing, impossibly colourful reality that is multi-layered, fragmented, and incredibly complete.

Share