Disintegration

By Liza David

Arts Illustrated's Short Story Contest, Second Runner-Up

He didn’t see it coming. Everyone seemed to know more about what was coming than he did. The neighbours knew, a few friends may have sensed it, the shopkeeper down the street maybe knew and she definitely knew. But, as self- assured as he seemed, he didn’t see it coming until the final moments when she dragged her stuffed suitcases and open boxes out the front door. The times they had known of what he thought were intimate were on drug-induced stupors or drunken evenings spent with take-away boxes. Sometimes pizza, mostly biriyani. He thought everything was okay, but then he always did. That was his way of making sure everything was always okay.

You’d recognise Merwyn by the slight limp in his gait; his left knee needed a surgery that he refused to get because he had no steady job and couldn’t afford it. His friends called him Merv, so did Mrin, and the neighbours, and the shopkeeper where he frequented for beer and cigarettes, and occasionally for fruit and vegetables also. Merv often said that he liked to eat healthy food and spent an awful lot of time making sure his face was well groomed and his shirts were ironed. The neighbours didn’t need to know everything, he told Mrin on several days. She hadn’t told them anything but when neighbours hear loud arguments and things being shattered, they tend to know. Mrin’s normal voice was quite loud in itself and then she went and frequently used language that was quite unpleasant for anyone to hear, though she frequently told Merv not to swear in front of her grandmother or at strangers while he was driving. Home was okay for name calling and fights. Everything had to look good on the outside. That was her way of making sure everything was always okay.

They’d met at the artist Ven’s place, up in the hills, a place frequented by loners and misfits of all stripes – people who thought they were alone and wanted to leave the city to be alone but knowingly, unknowingly, gathered in spaces where other loners and people at the fringes of social acceptance gathered. The last time they were up there they’d been on one of their drug-induced binges; mostly herbs, even medicinal, but sometimes liquids and pink crystals and white powders that smelled like a chemistry lab and created temporary euphoria and feelings of awe and wonder and connectedness. Ven had given them the sculpture of ‘The Thinker’ as a present. They both loved it. Perhaps even more reason why Merv didn’t see anything coming.

Merv grew up having to act like everything was always okay. Even when he was teased by friends for kissing a girl on a mountain top near school. Even when his dad died. Even when he had to move cities after that and struggled through school, with his mom hovering over his shoulder all the time. Even when he struggled to finish his engineering degree, that great struggle that many of our generation face, as if accomplishment and satisfied parents are a result of finally being called an Engineer. Most can barely engineer their happiness afterward. Anyway, he didn’t finish that all-important engineering degree, much to the dismay of his mother who then used up a handsome sum to send him off to a college abroad to get a degree in business. Even with that degree, there were days spent cleaning shop floors and nights spent dumping out-of-date food into large bins that the poor and homeless couldn’t access.

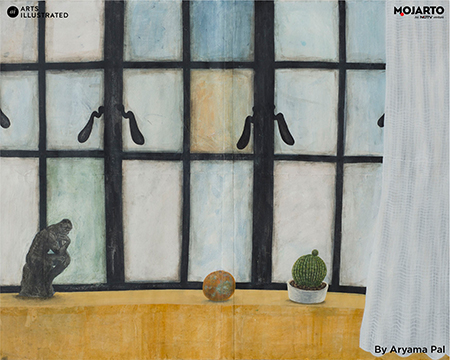

Meeting Mrin was a breath of fresh air because she had many emotions that she almost always acted upon. Maybe too quick and too often. Maybe he should have seen it coming. Now that they were married, surely everything was truly okay. Merv thought the marriage even made up for the lost engineering degree and the disappointed mom and that he could finally rest in the safe folds of a social contract, signed and sealed and delivered with religious and government authority. Nothing to do now but watch a game, eat healthy food when possible, always ensure his shirts are ironed and the yellow windowsill was dust free. Of course, take the occasional trip to Ven’s in the hills. Nothing more to it.

Mrin had been acting out more often though; even in the hills she was sobbing and seemed to be saying strange things. Was he supposed to take the vague hints of unhappiness that were turning into despair as something more than mood swings? It must have been her work stress. He knew she was in therapy. He hated therapists. His mom had once dragged him to one because he couldn’t finish the damn engineering degree. Besides, he wasn’t working again and all she did was ruin his time watching the game and disrupt his nap and never maintain his painstaking window cleaning. When she yelled, she roared all kinds of cruel things that she hoped the shut windows would block from neighbourly ears. Mrinalini Goswamy, a storm of a woman who flew into stormy rages and stormed out one rainy day. How dare she.

Her bags and boxes were packed slowly over the weeks before she left, the weeks she’d spent curled up on a mattress on the floor in the next room. Some nights she seemed to be imploring him to understand something, something about being ill, something about being terribly unhappy. In her final flurry, there was no space for the fossil rock that he’d found for her on a beach. She’d have loved to keep the sculpture but left it for him. Surely he would look after the cacti. Sod the cacti and the curtains made from old sarees. She shut the windows tight that day and dragged her teary face and over-stuffed bags out the door. He couldn’t stop her leaving.

About Liza David

Liza is a designer, researcher and design educator who has served as visiting faulty at NID Bengaluru. Liza also runs a mental health collective (ahorsewithnoname.in) with a few friends, in an attempt to create, collaborate and share safe spaces.